To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

That’s a great quote.

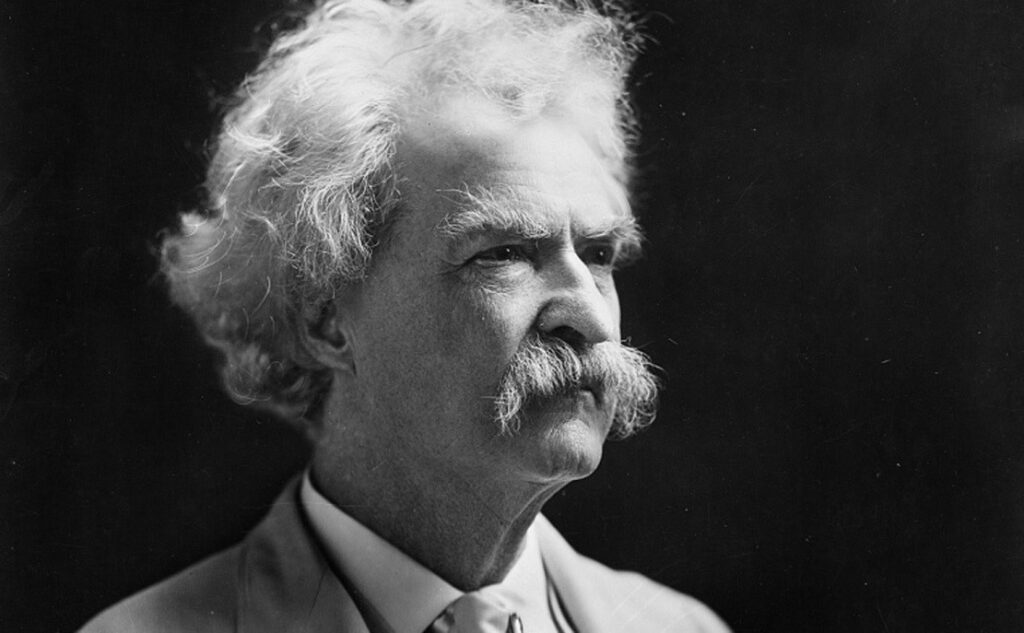

Those 21 words are routinely attributed to Mark Twain. In fact, I attributed them to Twain in a reflection a number of years ago. So did the director of The Big Short, who displayed the quote and Twain’s name in the 2015 film’s opening frames. Likewise Al Gore, who made good use of the quote nine years earlier in his award-winning An Inconvenient Truth.

There’s an inconvenient truth, however, concerning this famous nugget of wisdom from Mark Twain:

There’s absolutely no evidence he actually said it.

Which, when you think about it, is a wonderful illustration of the very danger these words are warning us about.

British language expert Nigel Rees, in an article in Forbes, traces the history of this memorable quotation.

It was originally published by American humorist Josh Billings in 1874. But Twain is far better known than Billings. And besides, it sounds like something Twain should have said. Thus it gradually became “his.”

Walter Mondale even got in on the act. During 1984, when he was running for president, Mondale said, “I’m reminded a little bit of what Will Rogers once said of [Herbert] Hoover. He said, ‘It’s not what he doesn’t know that bothers me, it’s what he knows for sure that just ain’t so.’”

So now we have a third party attributing a mangled quote to the wrong person in the wrong context.

At this point Bible skeptics smile knowingly. If it’s this hard to nail down the source of just 21 words only about a century ago, who in their right mind would trust the literary integrity of words written 2,000 years ago?

Some liken the evolution of Scripture to the game of Telephone that can be so amusing at parties.

Maybe you’ve played it. Everyone gets into a line. Someone whispers a sentence into the ear of the first person, who them whispers it to the second, and so on down the line. The fun is revealing what the last person hears compared to the original message. The more people who play, the crazier the distortions become.

The odds are pretty good that if you’ve ever held a Bible in your hands, you’ve wondered if you’re holding nothing more than the “final product” of a first century game of Telephone – the semi-garbled reconstruction of an original message that can never be satisfactorily recovered.

So, if God really spoke a message (or The Message) to somebody a long time ago, how in the world can we trust that sloppy human intermediaries haven’t fumbled the words on their long journey to our ears?

Here’s what the apostle Paul had to say:

“The first thing I did was place before you what was placed so emphatically before me: that the Messiah died for our sins, exactly as Scripture tells it; that he was buried; that he was raised from death on the third day, again exactly as Scripture says; that he presented himself alive to Peter, then to his closest followers, and later to more than 500 of his followers all at the same time, most of them still around (although a few have since died); that he then spent time with James and the rest of those he commissioned to represent him; and that he finally presented himself alive to me” (I Corinthians 15:3-7).

What’s Paul telling us here?

Let’s return to the game of Telephone.

Things would be very different (though not nearly as much fun) if we changed one of the rules. What if the first person was free to move down the line and occasionally listen in on what was being reported? The first person could interrupt and say, “Yes, you’ve got that part right, but I definitely never said this.”

There is every reason to believe that’s what happened during the earliest years of the church. Recent research on the phenomenon of oral tradition in the Middle East has revealed that a community committed to keeping alive an important story would take great pains to preserve the key details of that story.

Even to this day, in small villages in the developing world, there are certain respected members of the community who are empowered to say, “Yes, that is how the story goes, but these details are not quite right.” Studies show that such a self-correcting mechanism in an ancient oral culture ensured that the right things were remembered for the right reasons.

What Christians believe is that Jesus’ first followers received the original Message firsthand. They told it to a great many people and ultimately put their memories into print, choosing to be publicly accountable along the way to fellow apostles like Peter, James, and John (not to mention the whopping 500 other early witnesses who could be consulted in the pursuit of accuracy).

Does all this really matter?

It matters if we want to know where we stand with God in this world and the next. Did Jesus really defeat Death – the greatest enemy any of us will ever face – on the first Easter?

We truly need to know what we really know, and how we know that we actually know it.

Mark Twain could hardly have said it better.