To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

Each day this Lent we’re looking at major “turning points” in Christian history – moments or seasons in which the story of God’s people took an important and often unexpected turn.

It should have been an open-and-shut case.

Did a 24-year-old phys ed teacher named John T. Scopes teach evolution when he served as a substitute in a biology class in the small town of Dayton, Tennessee?

Early in 1925, the state legislature had passed a controversial bill: “It shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the universities… and all other public schools of the State … to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Any teacher found guilty of this misdemeanor would be fined between $100 and $500.

No one doubted that Scopes was guilty. He openly admitted what he had done.

But America was in the early stages of a culture war that would still be raging 100 years later – that is, right up to this morning. Secular groups like the American Civil Liberties Union wanted a test case: Could a state actually mandate the teaching of the biblical doctrine of creation, in defiance of the views of a majority of scientists?

A number of Christians wanted their day in court as well. Conservatives were convinced that disciples of Jesus could more than hold their own against disciples of Charles Darwin. A public showdown might prove to be splendid P.R. victory for the faith.

One group in particular stepped into the spotlight.

Their identity had been forged at the Niagara Bible Conference back in 1895, where leaders underlined five “essentials” of the faith: the inerrancy of Scripture, Jesus’ atoning death on the cross, his resurrection, his future Second Coming, and his supernatural conception in the womb of Mary – all of which served as proof of his divinity. “Real” Christians needed to sign off on these doctrines.

Between 1910 and 1915, two wealthy brothers – Lyman and Milton Stewart – commissioned Bible scholars to write a series of articles on the essentials that were published in 12 short volumes. These booklets were then distributed free of charge to virtually every pastor and Sunday School teacher in America.

The series was called The Fundamentals. People who subscribed to their perspectives became known as fundamentalists.

At the beginning of the Scopes proceedings, a fundamentalist was someone who took seriously the core teachings of the Bible. By the time things wrapped up, however, the word “fundamentalist” had become, in the minds of many, a derisive label to designate an uninformed, mean-spirited, closed-minded fool.

The “monkey trial,” as it came to be known, proved to be a public relations disaster for conservative Christians, from which it would take most of the 20th century to recover.

The town fathers of Dayton, Tennessee, relished the opportunity to become the center of the nation’s attention. Scopes, who was certainly not a radical, was talked into breaking the law. When he was duly charged with teaching evolution, more than 100 journalists descended on the village.

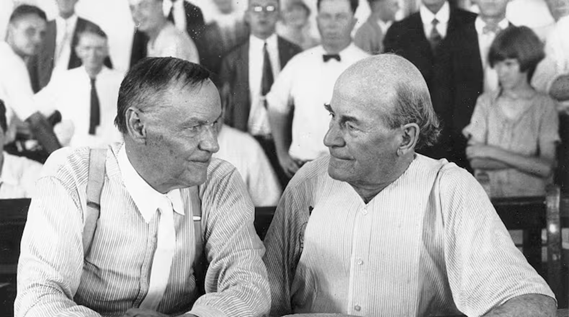

Two national celebrities showed up as well. One was Clarence Darrow (seated on the left in the picture above), America’s most famous labor lawyer and an outspoken agnostic. The other was William Jennings Bryan (seated on the right), a three-time presidential candidate and secretary of state under Woodrow Wilson. Darrow volunteered his services to Scopes’ defense team. Bryan declared that he would defend Scripture.

The trial convened in the middle of July 1925.

It was the first courtroom drama ever broadcast to a national radio audience, and it quickly became clear that the press had embraced some stereotypes.

Darrow, the agnostic, came to symbolize objectivity, tolerance, and clear-headedness – the bright hopes of America’s future. Bryan, the Bible thumper, embodied social awkwardness, religious bigotry, and the regrettable shadows of an era whose time had definitely come and gone.

About a week into the trial, Darrow goaded Bryan into taking the stand as an “expert witness” for the Bible.

Things did not go well.

Darrow was fully prepared to humiliate the older man, who was clearly suffering the effects of old age and a sweltering courtroom in the pre-air-conditioning era. He pressed Bryan concerning details in the Genesis account of creation, the big fish that swallowed Jonah, and the date of Noah’s Flood.

Darrow (concerning the date): “What do you think that the Bible, itself, says?”

Bryan: “I never made a calculation.”

Darrow: “What do you think?”

Bryan: “I do not think about things I don’t think about.”

Darrow: “Do you think about things you do think about?”

Bryan: “Well, sometimes.”

That generated a round of laughter in the courtroom. Those gathered were generally sympathetic with Bryan’s fundamentalism, but it was clear that Darrow was running circles around him. As historians have since pointed out, he undoubtedly could have run circles around Darwinists if they had been on the stand.

At one point the prosecuting attorney, a man named Stewart, interrupted Darrow’s relentless questioning: “What is the purpose of this examination?”

Bryan himself responded, “The purpose is to cast ridicule on everybody who believes in the Bible, and I am perfectly willing that the world shall know that these gentlemen have no other purpose than ridiculing every Christian who believes in the Bible.”

Darrow pounced: “We have the purpose of preventing bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the education of the United States and you know it, that is all.”

Bryan replied, “I am simply trying to protect the Word of God against the greatest atheist or agnostic in the United States,” which produced enthusiastic applause.

Everyone knew how the trial was going to end. Darrow even sarcastically said to the judge on the last day, “I think to save time we will ask the Court to… instruct the jury to find the defendant guilty.” After a mere eight minutes of deliberation, Scopes was convicted of teaching evolution. He was fined $100.

Conservative Christians won the battle. But they clearly lost the war.

As a journalist for The Nation put it, “Among fundamentalist rank and file, profundity of intellect is not too prevalent.”

Bryan, always generous, offered to pay Scopes’ fine. But the trial seemed to drain the very life out of him. He died on July 26, less than a week after the final gavel.

Something in the fundamentalist movement seemed to die as well. Could modern science and Scripture be reconciled? Most Christians thought so. But how could a literal reading of Genesis ever be reconciled with the claims of Darwinism?

Fundamentalism went into a kind of societal hibernation. It did not begin to re-enter the realms of politics, entertainment, and education in a significant way until the 1980s.

One hundred years after the Scopes trial, is it too late to put the “fun” back into “fundamentalist”?

People of good will can disagree on the identity of Christianity’s essentials. But no one should disagree that it makes sense to build our lives around the core truths of the life, death, and resurrection of God’s Son – and then to immerse ourselves in a community of fellow believers who will hold us accountable to living faithfully.

We already know the verdict on that.

It is deeply wise.