It’s often said that before we can hope to understand someone else’s life, we need to walk a mile in their shoes.

Or perhaps join them on a car ride from Washington D.C. to Texas.

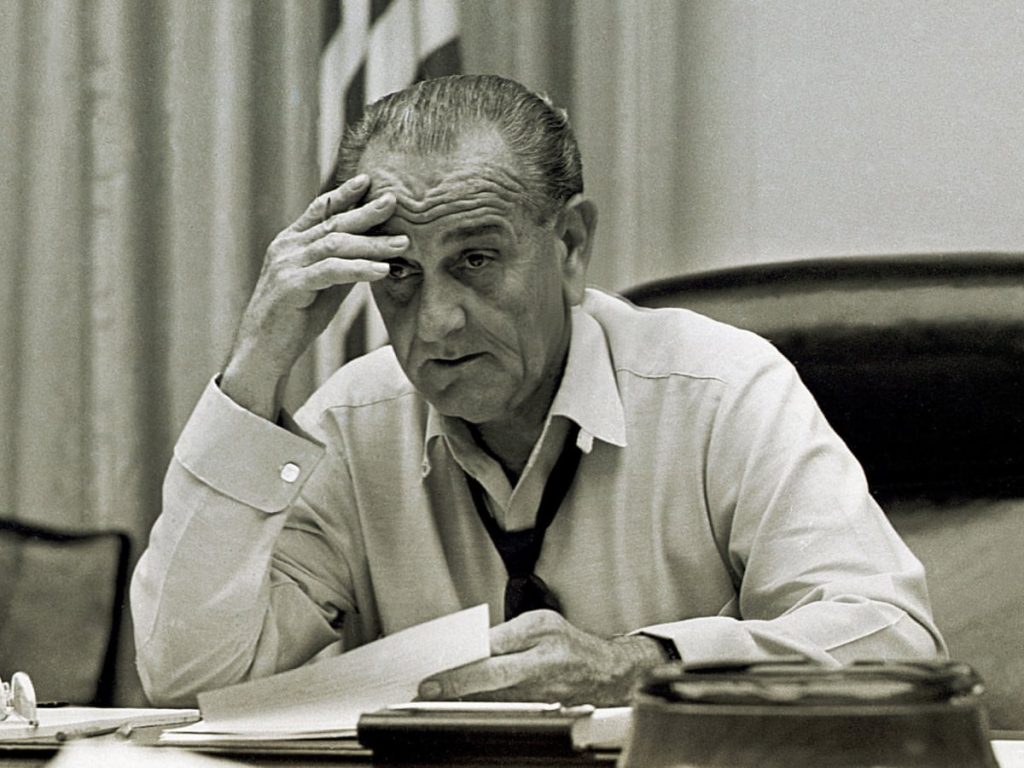

Before he became vice-president and ascended to the White House following JFK’s assassination in November 1963, Texas senator Lyndon B. Johnson sometimes asked his black housemaid and butler, Helen and Gene Williams, to drive his spare car from the nation’s capital back to Austin. On one occasion he also asked if they would take along the family beagle.

Gene hesitated. LBJ wondered why. “The dog loves you,” he said, “and he shouldn’t give you any trouble.”

Johnson didn’t get it. Gene Williams decided it was time to help him understand. He described what it was like for a black couple to spend three days traversing the Deep South. Because of Jim Crow legislation that had been in place for three-quarters of a century, blacks couldn’t access the bathrooms, lunch counters, motels, swimming pools, theaters, restaurants, or even drinking fountains that were reserved for whites.

After driving for hours, the Williams would invest even more hours looking for a diner that would serve them. They would sometimes venture miles beyond the highway searching for a bathroom. Finding a hotel that would welcome them was inevitably a struggle.

Gene summarized, “A colored man’s got enough trouble getting across the South on his own, without having a dog along.”

LBJ’s eyes were opened. He had nothing to say to Gene.

As Doris Kearns Goodwin notes in her book Leadership in Turbulent Times, Johnson shared what he learned from the Williams over and over again as he talked with Southern leaders and diehard segregationists. He knew that facts and figures wouldn’t change hardened hearts. But a compelling story has the capacity to get under your skin. Wasn’t it time to eliminate the sheer evil of the South’s systemic racial injustice?

President Kennedy had talked earnestly about civil rights. But he had failed to take decisive action.

Just five days after entering the Oval Office – and less than a year before the next national election – LBJ decided to risk his entire presidency on moving forward. When a friend suggested he would almost certainly be wasting his time and energy on a lost cause, Johnson responded, “Well, what the hell’s the presidency for?”

On November 27 he told Congress, “We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights. We have talked for 100 years or more. It is time now to write the next chapter, and to write it in the books of law.”

Goodwin declares that great leaders know what causes are worth risking everything for. They can discern the moment when it’s time to push all their chips to the center of the table.

LBJ knew what it would cost. “It was destined to set me apart forever from the South.” He was risking his reputation, his political career, and lifelong friendships.

He acted anyways.

The result was the Civil Rights Act of 1964, America’s first major legislative effort to address the injustices and social humiliations targeting people of color.

Empathy always costs something. As the apostle Paul writes, “Put yourself aside, and help others get ahead. Don’t be obsessed with getting your own advantage. Forget yourselves long enough to lend a helping hand.” (Philippians 2:4, The Message)

What in the world would prompt us to live like that?

We have a great role model.

Look at Paul’s very next verse: “Think of yourselves the way Christ Jesus thought of himself. He had equal status with God but didn’t think so much of himself that he had to cling to the advantages of that status no matter what.”

Walk in someone else’s shoes. Imagine what’s it like to live their life and face their challenges.

Then ask our empathetic Savior to fill you with the kind of empathy that will help transform this broken world.