The year 1968 had already been traumatic.

In January, the Tet Offensive had awakened America to the hopelessness of Vietnam. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were felled by assassins’ bullets during the spring. The summer was racked by rioting and protests, Czechoslovakia’s futile revolt against the Soviet Union, and the chaos of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

The turbulence continued that fall at the Mexico City Olympics.

Two black American sprinters – John Carlos and Tommy Smith, both of San Jose State University – planned to protest racial injustice on the medal stand. But first they had to win medals. On October 16, they shot out of the blocks in the final of the 200 Meters. Carlos took the lead. Heading for the finish line, Smith overtook him and captured the gold, setting a new world record. Carlos settled for the bronze.

What neither of them expected is that a third runner, Peter Norman of Australia – a white man – would run the race of his life and grab the silver.

The two Americans were participants in the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Before his death, MLK had been an advisor. Now their plan was to make a statement. Peacefully but dramatically, they would protest the systemic racism that looked the other way when they were called monkeys, when bananas were thrown onto the track, and when black athletes at SJSU were rarely given access to student housing.

During the few minutes between the end of the race and the medal ceremony, Smith and Carlos told the second-place finisher what they planned to do.

They asked Norman if he believed in human rights. He said he did. Australia at the time was being convulsed by its own racial struggles. Blacks, in fact, wouldn’t be granted the right the vote until the early 1970s.

Then they asked Norman if he believed in God. The Australian didn’t hesitate. His parents were on the staff of the Salvation Army. His faith was deep. When the two Americans explained their conviction that God had called them to stand up for human rights, Norman said, “I’ll stand with you.” Carlos later said that he expected to see fear in Norman’s eyes. Instead, “I saw love.”

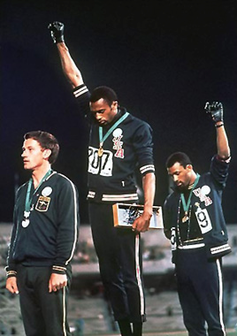

Smith and Carlos shared a single pair of black leather gloves. As they stood on the platform, the gold medal winner bowed his head and raised his gloved right hand. Carlos bowed his head and raised his gloved left hand. While The Star-Spangled Banner played, millions of Americans watching on TV vowed they would never forgive them. The U.S. Olympic Committee immediately suspended the pair and ordered them to leave Mexico City within 48 hours.

Peter Norman, meanwhile, stood calmly and looked straight ahead.

But he was wearing something on his uniform. On his way to the platform, he had borrowed an Olympic Project for Human Rights button from another American. That was his way of standing with Carlos and Smith.

That simple act upended his life.

Back home, he faced a tidal wave of scorn. He became a pariah and an outcast from everyone associated with track and field, the only sports community he had ever known. Though he qualified for the 1972 Munich Olympics, he was refused a place on the national team. His country even denied him ceremonial participation in their own Sydney Olympics in 2000.

Ironically, Norman ended up attending the Sydney Olympics as the honorary member of another nation. He was invited to join the American Olympic team.

By the year 2000, American feelings toward John Carlos and Tommy Smith had softened. They, too, had paid dearly for their public protest. Their athletic aspirations had been dashed. Doors of opportunity closed in their faces. But three decades later, in the minds of most, it was clear they had been on the right side of history.

Peter Norman died unexpectedly in 2006. Smith and Carlos flew to Australia, where they each spoke at his funeral and helped carry his coffin. It was only in 2012, six years later, that the Australian government finally apologized to Norman and his family, admitting they should never have ostracized one of their national heroes.

Carlos reflected at the time: “There’s no one in the nation of Australia that should be honored, recognized, appreciated more than Peter Norman for his humanitarian concerns, his character, his strength, and his willingness to be a sacrificial lamb for justice.”

In 2003, San Jose State University unveiled a statue of the 200 Meters medal stand from the 1968 Olympics. Smith and Carlos are standing silently, making their protest. But the plinth for the silver medalist, where Norman stood, is unoccupied.

That’s just the way the Australian wanted it. When he spoke at the statue’s dedication, Norman said he hoped that viewers would imagine themselves filling that empty spot.

Martin Luther King, Jr. declared that it’s not enough just to see what is happening. We need to speak up. And it’s not enough just to speak up. We need to stand up.

Powered by God’s grace and strength, will you help God heal this broken world?

Where will you stand today?