Throughout Lent, we’re exploring the parables of Jesus – the two dozen or so stories that were his chief means of describing the reality of God’s rule on earth.

Cambridge biology professor Richard Dawkins feels comfortably certain that God does not exist.

And he’s not impressed with people who believe otherwise.

“Faith is one of the world’s great evils,” Dawkins writes, “comparable to the smallpox virus but harder to eradicate… Religion is capable of driving people to such dangerous folly that faith seems to me to qualify as a kind of mental illness.”

He is particularly unimpressed with the God of the Old Testament, whom he describes as “arguably the most unpleasant character in all of fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynist, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully.”

As you might guess, Professor Dawkins is not routinely invited to provide keynote addresses at church conferences.

It’s an open secret, however, that more than a few Christians and Jews also struggle with the way God is portrayed in the first 39 books of the Bible. What are we to make of his commands to wipe out Canaan’s indigenous people groups; his verdict of capital punishment for children who publicly disobey their parents; and the way he sometimes seems to hold grudges against the female half of humanity?

One of the earliest figures in the history of Christianity, a teacher by the name of Marcion, was so offended by such things that he concluded the “God” behind the Old Testament simply had to be evil. He had created a ramshackle world and was doing a very poor job as its Managing Director.

Marcion recommended that the God portrayed in Genesis, Exodus, Joshua, and the Psalms be fired for cause. Followers of Jesus didn’t need to bother reading the Hebrew scriptures, even though Jesus himself had clearly been in love with them.

For his radical opinions, Marcion was branded a heretic and excommunicated from the church in A.D. 144.

That may have extinguished the controversy. But it failed to fully address the important underlying question: If Jesus is God (as he himself claimed, and as Christian creeds have always asserted), does that mean that Jesus gives thumbs up to all the darkest and most difficult parts of the Old Testament? Is our present life supposed to represent a continuation of those narratives?

That’s been a stumbling block for many people who sincerely want to know what kind of Savior he is.

Perhaps it will help to consider a pair of equations: (1) Jesus = God. (2) God = Jesus.

If you remember your fundamental principles of mathematics (and who doesn’t want to be reminded of those on a March morning), this seems to be an illustration of the commutative property. Whatever appears on the left side of an equation (usually expressed as the sum of two or more numbers) is always equal to whatever appears on the right side of the equation, as long as the very same numbers are added together. In other words: If A + B = B + A, then B + A = A + B. Simple and straightforward.

But things are not quite so simple when it comes to Gospel arithmetic.

Theologians believe that equations (1) and (2) above are both true. But they are actually making different statements – and that difference is well worth exploring.

Jesus = God is simply astonishing. When you think of Jesus, think of God. He embodies the fullness of the divine attributes (Colossians 2:9-10). Christians would say that the only human being about whom we have ever been able to make such a claim is Jesus of Nazareth.

God = Jesus, on the other hand, is nothing less than the key to understanding his entire ministry. When you think of God, think of Jesus. This addresses our toughest questions about God’s character and identity. What is God really like? Is he our enemy or our friend? Is he a heavenly Accountant tallying up sins or a gracious Father yearning for his children to come home?

Jesus’ heartfelt stories cut through the fog. That’s why, when we think of God, we don’t start with the book of Judges. We start with the Parable of the Prodigal Son.

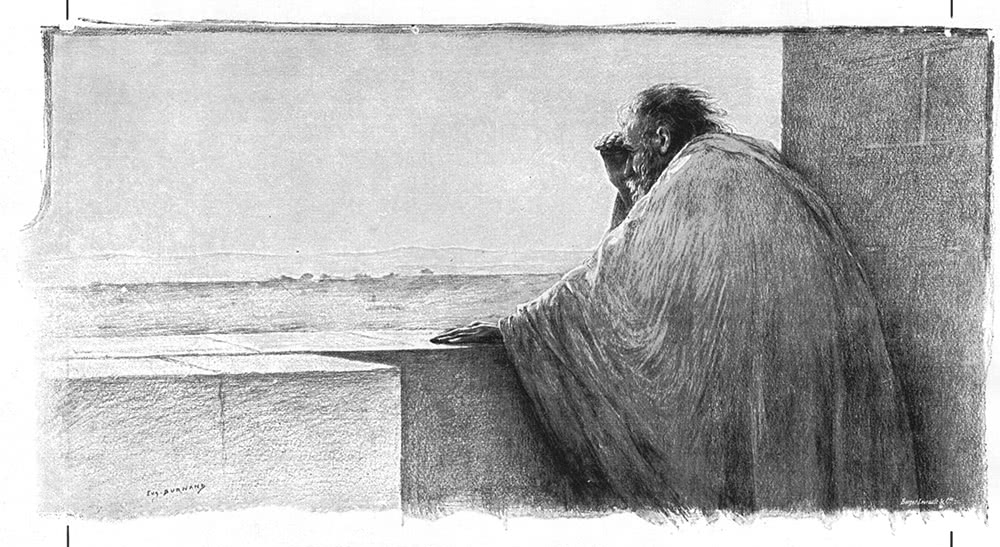

The German theologian Helmut Thielicke once wrote that it’s a great pity that Christians ended up naming this parable after the kid who makes a train wreck out of his life. He suggested it be called the Parable of the Waiting Father.

The hero of the story, after all, is God the Father. He lets his child go. Then he yearns for his return. When he sees him coming down the path – broken and disillusioned – he runs to embrace him. He doesn’t care what the neighbors think. Then he pleads with his older son – the one who is too proud to surrender his self-righteousness – to join him in celebrating his brother’s return. And if the neighbors are tsk-tsking behind his back that he’s being a pushover by not ordering that son to come in and help host the party, he doesn’t care about that, either.

God is the hero of every story. Life always comes down to who God is, what he has done, and what he might to do next.

And what is this God like?

When you think of God, think of Jesus.

Think especially of the story in which Jesus makes it absolutely clear that the Father’s door is open to us all.

Even prodigals, religious stuffed shirts, and skeptical biology professors.