Throughout Lent, we’re exploring the parables of Jesus – the two dozen or so stories that were his chief means of describing the reality of God’s rule on earth.

For a book written between two and three millennia ago by at least 40 human authors, the Bible is remarkably accessible for readers of all ages and cultural backgrounds.

Then there are the head-scratching texts.

Twenty-first century readers struggle to figure out who Cain might have married (since he is presented as the only surviving child of Adam and Eve); why God would tell the people of Israel not to wear garments combining two different kinds of cloth; and what we’re supposed to make of the adulterous, drunken woman sitting on a scarlet beast with seven heads and ten horns in Revelation 17.

Mark Twain surely had it right when he said that he wasn’t overly concerned about the Bible verses he didn’t understand. He had his hands full with the ones he understood perfectly well.

Nevertheless, our call isn’t to skip the hard parts. The respected scholar N.T. Wright admits that while we can’t live without the Bible, from time to time the Bible can be pretty hard to live with, too.

He puts it like this: “In the last generation we have seen the Bible used and abused, debated, dumped, vilified, vindicated, torn up by scholars, stuck back together again by other scholars, preached from, preached against, placed on a pedestal, trampled underfoot, and generally treated the way professional tennis players treat the ball. The more you want to win a point, the harder you hit the poor thing.”

No story of Jesus has been more pummeled than the Parable of the Shrewd Manager. Some Bible students have come to the conclusion these verses are so problematic there’s no way we can get Jesus off the hook. The Roman emperor Julian the Apostate, no friend of the Church, used this parable to “prove” that paganism was morally superior to Christianity.

It’s time to see what all the fuss is about.

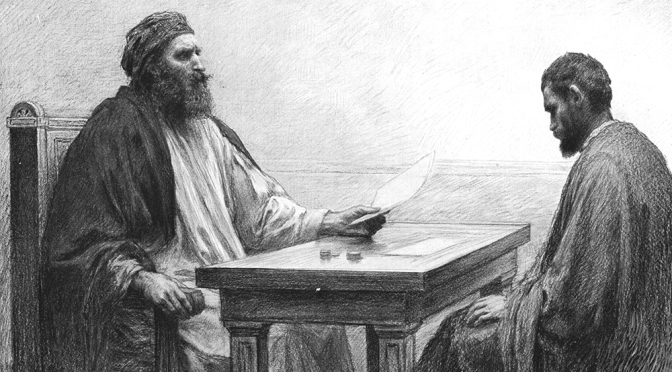

Jesus told his disciples: “There was a rich man whose manager was accused of wasting his possessions. So he called him in and asked, ‘What is this I hear about you? Give an account of your management, because you cannot be manager any longer.’ The manager said to himself, ‘What shall I do now? My master is taking away my job. I’m not strong enough to dig, and I’m ashamed to beg. I know what I’ll do so that, when I lose my job here, people will welcome me into their houses.’

“So he called in each one of his master’s debtors. He asked the first, ‘How much do you owe my master?’ ‘Eight hundred gallons of olive oil,’ he replied. The manager told him, ‘Take your bill, sit down quickly, and make it four hundred.’ “Then he asked the second, ‘And how much do you owe?’ ‘A thousand bushels of wheat,’ he replied. He told him, ‘Take your bill and make it eight hundred.’

“The master commended the dishonest manager because he had acted shrewdly. For the people of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own kind than are the people of the light. I tell you, use worldly wealth to gain friends for yourselves, so that when it is gone, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.” (Luke 16:1-9)

Check out that last verse again. Jesus appears to be saying, “I command you to use money to make friends.” If that’s so, then a lot of people we don’t particularly admire are way ahead of the curve in the kingdom of God. Jesus tells the story of a scoundrel who gets rich at the expense of his boss, and then has the audacity to say to his disciples, “Let this crook be your role model!”

How should we approach this parable?

First we need to acknowledge that in an oral culture like that of ancient Israel, every detail of a story is relevant. Jesus uses specific words and paints particular pictures for a reason. We also need to recognize the crucial role of the village. Those listening to the story for the first time would have found it easy to insert themselves into this mini-drama. They would know what it would feel like to live in the same town as this rich landowner and his manager.

That’s not nearly so easy for us. The back story is there for us to find, however, if we’re willing to do some homework. That can feel like hard work. But in the end it’s far more satisfying (and spiritually valuable) than simply gazing at these verses and sighing, “Well, this is what they mean to me.”

Our real hope is to find out what this story meant to Jesus and his original audience.

Here’s what we know: A rich man apparently owns a great deal of property. He employs a business manager who runs his affairs, keeps his accounts, meets with his clients, and collects his debts.

The master appears to be of noble character. He’s well-respected in the community. But the manager is cooking the books. Perhaps he’s accepting payments under the table. The master learns about this and asks, indignantly, “What is this I’m hearing about you? You’re finished, pal.”

Note that in the story the manager says nothing in response. He offers no alibis or explanations. In the Middle East such silence is huge. It screams that he is guilty, and now he knows that the master knows he is guilty. He has no leg to stand on. His future looks bleak.

In our day and age (at least before we began working from home), if you were found guilty of financial mismanagement, some folks from Personnel and Security might come and ask for your swipe key. They would demand that you turn over your laptop and clean out your desk on the spot, then escort you to the lobby. You might even be led away in handcuffs.

In Jesus’ parable, the master has fired the manager and ordered him to turn in his financial records. “What am I going to do now?” he asks himself.

Everyone in the village will know within one hour that he has lost his job. Therefore the manager has to act quickly. He reviews his options. If he expects to eat, he may have to resort to digging. But manual labor was hard, and it was also considered beneath the dignity of an educated person. How about begging? He would die of the shame. How can he deal with the fact that his public image as a professional is about to be compromised beyond repair?

Cultural scholar Kenneth Bailey suggests that within a matter of minutes, this scheming fellow formulates a plan.

He will risk everything on the mercy of his master. If he fails, he’s on his way to jail. But if he succeeds, he just might become a hero in the community and make his master look good in the process.

The manager cannot save himself. He knows that. But he cleverly devises a situation – he takes a huge risk – to see if his master, given the chance, just might come to his rescue.

Tomorrow we’ll check out what he decides to do.

In the meantime, ponder this question:

Would I be willing to be bet my whole life that God will take care of me, even when I know I’m not the person I should be?