There is general consensus that the finest ceramics Western artisans have ever produced came from the workshop of Josiah Wedgwood.

Wedgwood (1730-1795) was either the 11th or 13th child born into his middle class British family – historians still debate the point.

What no one debates is that his artistic gifts and entrepreneurial spirit became powerful drivers in the Industrial Revolution. He’s credited with almost singlehandedly inventing marketing ploys that today we take for granted: money back guarantees, free delivery, buy-one-get-one-free, and direct mail solicitation through illustrated catalogues. The next time Amazon or FedEx leaves a package on your front porch, you can thank Josiah Wedgewood.

He perfected the creamy azure background that became known as “Wedgwood blue.” A semi-three-dimensional bas relief, or cameo (usually white) was typically featured, depicting images of kings, queens, mythological figures, or various aspects of daily life in 18th century England.

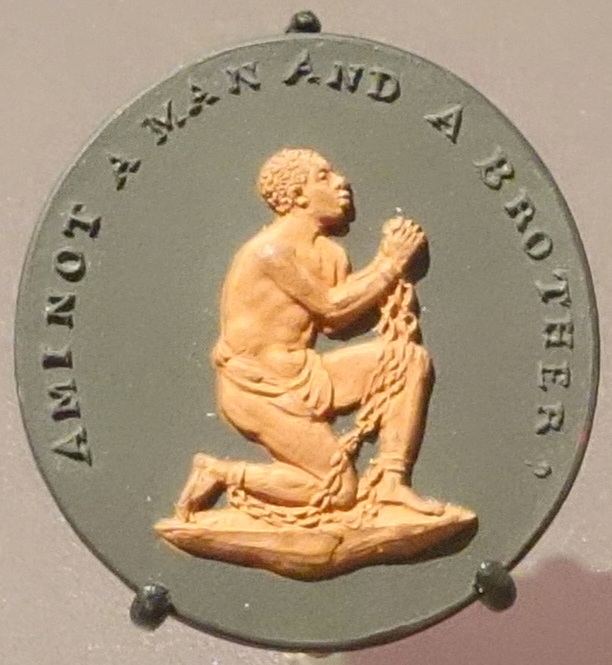

But the most famous Wedgwood engraving of all time was a humble figure produced in 1787.

A kneeling black slave, chained from his wrists to his ankles, asks this poignant question: “Am I not a man and a brother?”

Wedgwood was an ardent abolitionist. He despised the fact that Britain’s economy was built on the African slave trade. The prices of key staples were kept low because unpaid laborers worked the cotton fields of the American colonies and the brutal sugar plantations of the Caribbean. Parliament’s ruling powers had little to no incentive to change the status quo.

Wedgwood’s provocative question challenged that.

British historian Joseph Hothschild suggests that the Slave Medallion was the first logo ever designed to advance a political cause. Wedgwood made thousands of copies. Men who were sympathetic to the abolitionist cause purchased snuff boxes adorned with the engraving. Women displayed bracelets and hairpins. The image appeared on tobacco pipes, and large-scale reproductions were hung up as posters. Historian David Dabydeen of BBC History believes that this single engraving represented “the most famous image of a black person in all of 18th century art.”

Wedgwood died almost 40 years before slavery was made illegal in the British Empire, and 70 years before the United States finally did the same.

But his famous medallion almost certainly helped advance the conversation. That’s because the slave’s two-part question strikes at the heart of slavery itself: Am I not a man and a brother?

“Enlightened” people in the 21st century may assume these are no longer cutting-edge issues. But for centuries some of the most authoritative voices in our culture – self-described scientists and theologians – have publicly declared that the answer to both questions is No. Black Africans are not fully human. And they are not genuinely equal as Christian brothers and sisters.

On this first day of Black History Month, it’s worth exploring what Josiah Wedgwood was up against.

Racial bias has afflicted virtually every human culture and civilization. Since it involves questioning the essential worth of fellow human beings, it remains a painful and searing issue.

Sociologists have never come to agreement on the number of races, let alone what to call them. The Greek philosopher Aristotle was blunt: Slaves weren’t even members of homo sapiens. He described them as “human tools.” That view helped fuel the pseudo-scientific perspective (which could still be found in respectable journals before World War II) that blacks are somehow “less evolved” than white Europeans. After Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species appeared in 1859, biologists openly speculated that blacks are “savage, barbaric, and lacking restraint, like animals” – evidence that they were losers in Nature’s epic battle of competing species.

Respectable scientific research has demolished such reasoning. But myriad websites keep centuries-old biases alive.

What does scripture say?

“God created humanity in God’s own image, in the image of God he created them. Male and female God created them” (Genesis 1:27). Am I not a man? The Bible is crystal clear: All human beings bear the image of the Living God. That is the essence of our equality.

The struggle to address the second question, Am I not a brother? represents one of the most painful chapters in American Christianity.

Generations of preachers (and not exclusively those in the South) have performed exegetical gymnastics searching for verses that might endorse an overt or subtle subjugation of non-white races. Some have concluded that blacks do not really have souls – at least not souls as pure as those of white Europeans – and are therefore relegated to a second-class standing as sisters and brothers in Christ.

Is there slavery in the Bible? Absolutely. It’s estimated that one-third of those who lived in the Mediterranean world of the first century were slaves, and another one-third were former slaves. It seemed inconceivable that the Roman Empire could ever go forward without slave labor.

But there’s a world of difference between what the Bible reports and what it endorses.

The Good News of Jesus planted seeds – specifically, a vision of a world in which humanity’s traditional dividing lines would one day be erased within a new kind of community. “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28).

We are still far from the fulfillment of that vision. It’s taken a long time for the seeds to grow and flourish. But it is beyond dispute that Jesus has done more to liberate women than any other religious leader. And while certain preachers have indeed stoked the fires of racial bias, those who ultimately won the historical fight to abolish slavery were almost all motivated by their loyalty to Christ.

Josiah Wedgwood’s question still stands: Am I not a man and a brother?

Scripture resoundingly says, “Yes and Yes.”

It may be that God’s greatest work in our hearts and through our hands will be to help sweep away even the need for such a question in the future.