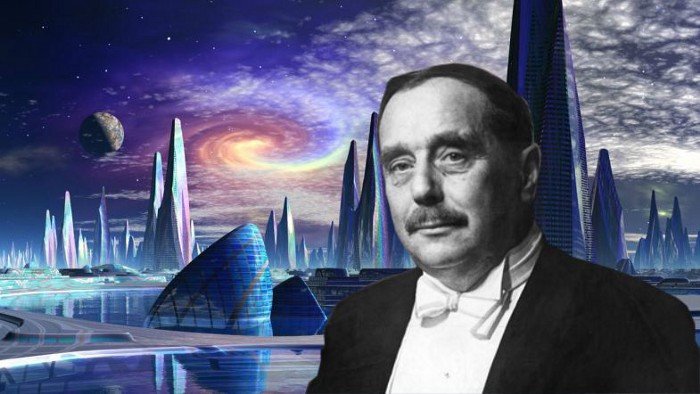

One hundred years ago, British author and philosopher H.G. Wells was one of the most lavishly optimistic thinkers on the planet.

In his 1922 book A Short History of the World, he envisioned the dawning of a golden age. Even though the horrors of World War I had ended only four years earlier, Wells was certain that science would soon usher in a time of global peace and justice. It was inevitable. It was humanity’s destiny.

He closed his book with this flourish: “Science has brought humanity such powers as he never had before… As of yet we are hardly in the dawn of human greatness. Can we doubt that our race will more than realize our boldest imaginations, that it will achieve unity and peace, that the children of our blood and lives will live in a world made more splendid and lovely than any palace or garden that we know, going on from strength to strength, in an ever-widening circle of adventure and achievement?”

The author of science thrillers like War of the Worlds and The Time Machine believed that human goodness and reason would conquer every problem.

A decade and a half later, however, as the long shadows of German Fascism fell across Europe, his faith began to waver. He wrote in 1939, “The wanton destruction of homes, the ruthless hounding of decent folk into exile, the bombings of open cities, the cold-blooded massacres of children… [have] come near to breaking my spirit altogether.”

Then things got worse.

Shortly before his death in 1945, just as World War II was staggering to its tragic finale, Wells wrote an essay called Mind at the End of Its Tether. “The human story has already come to an end. Homosapiens, as he has been pleased to call himself, has been played out.” Centuries of darkness lay ahead. His hope now lay in the extinction of humanity, after which a new species might arise that could better cope with the challenges of existence.

Some men, at the end of life, get surly and yell at the neighbors’ kids. “Get off my lawn!” The unraveling of H.G. Wells had considerably greater impact. His loss of hope mirrored a global loss of faith in the notion that tomorrow simply has be better than yesterday.

Where did that idea come from in the first place?

Robert Nesbitt, in his book History of the Idea of Progress, reveals that most ancient cultures were less than optimistic about the future. Life is hard and then you die. Christianity, however, introduced some hopeful new perspectives. The cosmos is ruled by a good and sovereign God. Life is hard, but everything matters. One day followers of Jesus will get to share in the new heavens and new earth made possible by the life, death, and resurrection of the Messiah. Life means something. And it’s going somewhere.

The “brightest and best” thinkers of the European Enlightenment (approximately 1750 to 1900) cherished the notion of progress. But they had little use for the idea of God. So they proposed a set of secular convictions that embodied the spirit of Little Orphan Annie: “The sun will come out tomorrow.” Life is getting better and better. Guaranteed. Place all your bets on reason and science.

But the same 20th century realities that broke the spirit of H.G. Wells made it increasingly hard to believe in the gospel of secular progress.

There were two world wars. And the great Flu Pandemic of 1918-19, which may have taken as many as 50 million lives. And the Great Depression. And Nazi death camps. And Hiroshima. And Pol Pot. And the Cold War.

Reason and science, which were supposed to come to the rescue, not only failed to root out human violence and oppression but proved to be the source of much of the pain. Secular philosophy has so far been powerless to provide hope. As British wit G.K. Chesterton once predicted, “The result of ceasing to believe in God is not that one will then believe nothing, but that one will believe anything.”

As we approach the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, the unwritten creed of the American Dream seems very much up for grabs.

There’s little hope that the next generation of children will automatically inherit better health, better jobs, and better lives than their parents. The members of so-called Generation Z appear to be considerably less inclined to marry, have children, and feel good about their future prospects than those who came before. News programs lead off with accounts of violence in Ukraine, new COVID-19 spikes, political polarization, the opioid crisis, and seemingly unstoppable gun violence.

We can’t live without hope. But where do we find it?

We return to the ancient truths that launched the ideas of progress and life-is-worth-living in the first place. First we discover the Bad News. Then comes the Good News.

The Bad News is that almost all the problems humanity faces aren’t out there somewhere. They’re in here – within our own hearts. We are not ignorant people in need of better education (although better education is always a good thing). We are not irrational people in need of sharper thinking (although, goodness knows, sharper thinking would definitely be a plus). We are sinful people – actively resistant to the One who gave us life and calls us to something higher than merely living for ourselves. Science and reason can never cure our crippled hearts.

But Jesus can. That’s the Good News.

Peter the apostle writes, “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! By his great mercy he has given us a new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead…” (I Peter 1:3). There’s lots more. But that’s where we start.

A living hope for the future is what God gives to everyone who welcomes his version of radical heart surgery.

That doesn’t guarantee that tomorrow will automatically be better than yesterday.

But it does mean that life’s finish line will be more incredible than we have ever dared to imagine.