To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

Throughout the season of Advent – which this year encompasses the four weeks leading up to December 25 – we’re looking at classic Christmas movies and how they might connect us to the miracle of God choosing to become a human being.

And finally, here at the end of the month, we come to a Christmas movie that actually endeavors to tell the story of why we even have Christmas.

We leave behind Santa Claus, flying reindeer, and kids trying to move the needle from naughty to nice. We come face to face with the claim that God entered space and time in the person of a vulnerable child – an infant born in the backwater province of the Roman Empire known as Judea.

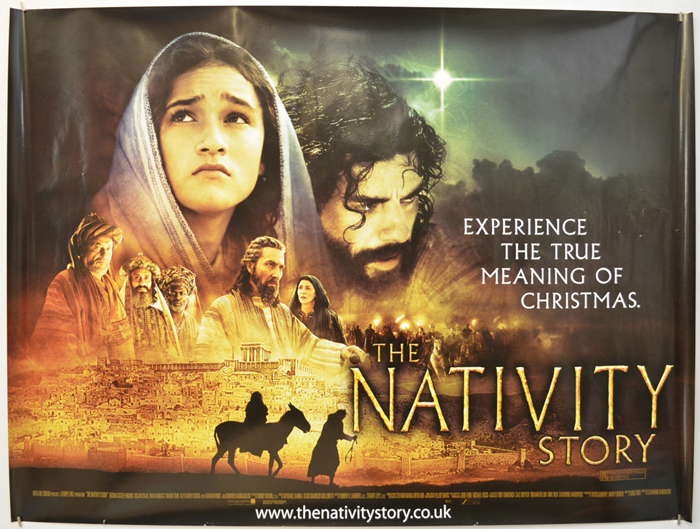

The Nativity Story is Hollywood’s most recent attempt to transform the gospel accounts into a feature-length film. It premiered in Vatican City on November 26, 2006 – the first movie ever to debut in the home of the Catholic Church.

Sixteen-year-old Keisha Castle-Hughes portrays Mary, while Oscar Isaac – who a decade later would achieve global stardom as Rebel pilot Poe Dameron in the Star Wars sequel trilogy – plays her faithful fiancé Joseph.

Most Bible readers cherish mental pictures (including ones they don’t even know they have) of the most famous scenes associated with Jesus’ birth. The power of a movie like The Nativity Story is that it challenges our perceptions. Generations of artists, for instance, have led us to assume that the angel Gabriel approaches Mary within the privacy of her home. The Nativity Story, however, places that signature event outdoors in an agricultural setting. Nothing in Luke’s text forbids such an interpretation. Here’s what it looks like in the movie: Gabriel Visits Mary – YouTube.

Gabriel in that scene actually looks as if he could have been a drummer in a 1970s rock band. Likewise, we may be surprised at Mary’s appearance. Here she has the look of an authentic first century Jewish teenage girl. There is no halo. Nor is she wearing the familiar blue cloak that we see in so many medieval paintings. She is a real person, not a porcelain figurine on our fireplace mantel this weekend.

The movie helps us think in a new way about the most famous “yes” in human history.

Replying to Gabriel’s mind-bending announcement that God is asking her to bear Israel’s long-awaited Messiah, Mary says, “I am the Lord’s servant. Let it happen to me just as you say” (Luke 1:38). It’s as if Mary is signing her name to the bottom of a blank sheet of paper – a covenant of heartfelt service – trusting that God will fill in all the details one day at a time.

It’s impossible to overstate what an act of courage this is.

Saying yes to God, in Mary’s case, also means saying no. She’s saying goodbye to her reputation. Unmarried, expectant teenagers in first century Israel didn’t get a guest spot on MTV’s 16 and Pregnant. They and their families got scorn and misunderstanding instead.

Mary is losing the honor game – the most important game in town. In an “honor culture” like that of the Middle East (then and now), people assume that only a finite amount of honor exists. There’s not enough to go around. If one person’s public esteem goes up, someone else’s has to go down.

Because Mary’s child will be publicly identified as a mamzer – the Hebrew term for a child from an illicit relationship – she and Jesus and Joseph will live under a cloud of shame for the rest of their lives, an association almost impossible to eradicate.

Mary is likewise saying no to her dreams of a quiet, pain-free life. After Jesus is born, a wise old man named Simeon will tell her that raising God’s Son will involve great suffering. “A sword will pierce your soul,” he assures her (Luke 2:35). This is not the kind of sentiment that inspires Christmas carols or a new line of Hallmark cards.

Why does she say yes?

Mary, who would no doubt have been dismissed in her own time as a nobody from Nowheresville, intuitively understands what so many of history’s brightest, best-educated figures never seem to comprehend: All of us are servants. The only real issue is whom or what we will choose to serve.

Bob Dylan won a Grammy for his song Gotta Serve Somebody. The refrain goes, “But you’re gonna have to serve somebody, yes indeed. You’re gonna have to serve somebody. Well, it may be the devil or it may be the Lord, but you’re gonna have to serve somebody.”

John Lennon, apparently irritated by such limited options, responded with a song of his own: Serve Yourself.

But all he did was prove Dylan’s point. You can give your ultimate loyalty to a global cause, to personal honor and advancement, to an ideal partner, to your 401(k), or to the absolute conviction that there’s nothing worth your ultimate loyalty – but you will definitely end up choosing to serve something.

Mary knows she is always going to be a servant. Therefore she decides, “I am the Lord’s servant.”

And that makes all the difference in the world.

It can make all the difference in the world for us, too.

Which is why we should endeavor this year and every year to have a Mary Christmas.