To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

At the beginning of this first full week of Black History Month, it’s clear America’s civil rights movement still has a long way to go.

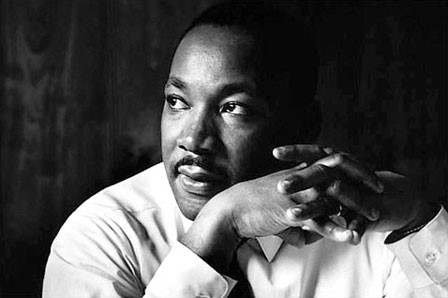

The unique gift of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s leadership continues to bear fruit, even in his absence.

But something else is missing from the landscape of contemporary civil rights activism: MLK’s resilient trust in God.

Lewis Baldwin, Professor of Religious Studies and Director of African American Studies at Vanderbilt University, points out that many labels were attached to King during his lifetime. “He was called a civil rights activist. He was called a social activist, a social change agent, a world figure. But I think he thought of himself first and foremost as a preacher, as a Christian pastor.”

His father was a pastor. His grandfather had been a pastor. His great-grandfather had been a pastor.

When King was called in 1954 to become the 20th pastor in the storied history of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, he expressed no aspirations to campaign openly for civil rights. The committee that hired him said they were looking for a “noncontroversial pastor” who could help heal internal church tensions and restore congregational morale. Baldwin reports, “King arrived with a 34-point plan for the future.” In other words, he would be just another exceedingly busy pastor.

The very next year, however, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery bus.

King plunged into organizing a bus boycott. The rest is civil rights history.

It’s clear that King never ceased to be who he truly was – someone who believed in the existence of an infinite-personal God, a creator who endowed all men and women with equal worth and dignity as co-bearers of his image, and who calls us, through Jesus, to confront social injustice with non-violent love.

“Every genuine expression of love grows out of a consistent and total surrender to God,” he wrote.

During his brief 13 years of public ministry, King was beaten, hit with stones, stabbed in the chest by a deranged woman, and imprisoned 29 times. J. Edgar Hoover called him “the most notorious liar in the country.” Like all of us, Dr. King was far from perfect. In the face of unremitting criticism, he doubled down on his trust in God. Nothing good, he said, could happen apart from clinging to the God whose mission he yearned to represent.

King biographer Taylor Branch has pointed out something crucial about the civil rights movement of the 50s and 60s. It “fused the political promise of equal votes with the spiritual doctrine of equal souls.”

And that highlights an important contrast with today’s civil rights conversation. For many contemporary activists – whether community organizers, politicians, or action groups – faith is no longer central. It may not even be in the picture. Millions of people who care about civil rights share Dr. King’s relentless trust in God. But when it comes to the public face of civil rights dialogue at the highest levels in our country, talking about God is clearly out of fashion.

Every activist agrees on the absolute need for equality and human rights.

But if God’s presence is no longer assumed, where exactly do these rights come from? If someone like God isn’t there to declare that human beings are equal, what makes us think such a thing is true? And if Jesus is just one voice among many spiritual traditions, why should we put ourselves at risk by imitating Dr. King’s radical dependence on Jesus’ non-violent methods?

Secularism is the worldview that dominates American university campuses and much of the 21st century’s social and political dialogue.

But secularists struggle when it comes to the so-called “moral question.” On the one hand, they insist there are no absolute values “out there” waiting to be discovered. That’s because there’s no God who is empowered to say, “This is right and this is wrong.” Human beings must therefore live by their own authority. We’re boldly challenged to create our own values.

At first glance, this formula seems to promise glorious freedom. But in actual practice, it leads to chaos.

When my favorite values conflict with your favorite values, and there’s no divine Authority to act as referee, who or what decides who “wins”?

Author Robert Nozick begins his much-admired book Anarchy, State, and Utopia with this oft-quoted line: “Individuals have rights, and there are some things no person or group can do to them.”

That’s a lovely idea. But an honest person has to respond, “Wait a minute: Who says?” Who can say – with authority – that individuals actually have rights? And does that mean non-Western people have to buy into the preferred rights of Western people if they don’t happen to like them?

Virtually everyone agrees that it would be a very good thing for as many people as possible to enjoy the Good Life.

But here again, secularism struggles. Who gets to decide what constitutes a “good” human life? Secular authors generally fall back on evolutionary biology (“good” is whatever propagates our species) or cultural relativity (“good” is what this group of people, at this moment in history, feel good about).

What do those two options have in common?

In both of them, morality is a moving target. Things like “right,” “wrong,” and “good” turn out to be relative. If our deepest core values are actually subject to change, then human rights may end up depending on our feelings or the results of the most recent election.

We can safely say that Dr. King cherished a dramatically different view of reality. He lived and breathed a set of bedrock spiritual convictions that, in the end, provided the moral foundation for America’s civil rights movement 60 years ago.

MLK quoted Amos 5:24 more than any other Bible verse: “But let justice roll down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream.”

What concept of justice is he talking about here? It’s the notion of justice that emerges from the Old and New Testaments, as embodied by the Hebrew Torah and Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. And whose righteousness is he talking about? Rather than clinging to cultural definitions of what is right and good, he is proclaiming God’s righteousness – God’s character as revealed in God’s Word.

As Dr. King himself once said:

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness. Only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate. Only love can do that.”

It won’t be our own faint light or our own untrustworthy love that will finally attain the most important goals of the civil rights movement.

But wonderful things will happen as we choose to align ourselves with the God who is Love and the Savior who is the Light of the World.