To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

Every day during this season of Lent we’re looking at one of the “3:16” verses of the Bible, spotlighting some of the significant theological statements that happen to fall on the 16th verse of the third chapter of a number of Old and New Testament books.

“Or why was I not hidden away in the ground like a stillborn child, like an infant who never saw the light of day?”

The book of Job, which is quite likely the oldest of the Bible’s 66 books, wrestles with what is quite likely the oldest of theological questions: Where is God when life hurts?

As the book opens, Job, the main character, is famous for his wealth and generosity. He is a good man who is living the Good Life. By the second chapter, however, Job has been crushed by a series of disasters. He has lost his children, his health, his net worth, and his certainty that life is fair.

His statement in Job 3:16 is shocking. If only I didn’t exist. If only I had never been born.

Is it possible to be both blessed and depressed? Is it possible to be suicidally despondent and still be living under God’s favor?

The book of Job answers that question. The answer is Yes.

Chapter after chapter, Job rails against God. He wants to know why his life has run off the rails. He demands answers. Divine intervention. Something. He never receives the fullness of what he seeks, but he does receive God’s commendation in the end. God never blames him for his doubts, his depression, or his rage. And that is something the Church, over the centuries, has struggled to take to heart.

During certain periods of Church history, suicide has been portrayed as an unforgivable sin. After all, how could someone ever ask for forgiveness after making such a desperate choice?

But consensus has emerged among both Catholics and Protestants that our weakness isn’t greater than God’s grace.

Everyone agrees that self-harm is the antithesis of God’s will. About two dozen suicides are reported on the pages of scripture, including King Saul, Samson, and Judas Iscariot, and not one of them is seen in a positive light. But we have no reason to believe that self-harm has the power to thrust someone beyond God’s mercy, especially at the moment of our greatest need.

Nor do we squander God’s blessing when we take full advantage of the medical advances that have brought so much relief to people who battle clinical depression.

The good news is that sadness, despondency, and hopelessness cannot separate us from the love of God. And there is much we can do to relieve the kind of anguish Job so obviously feels.

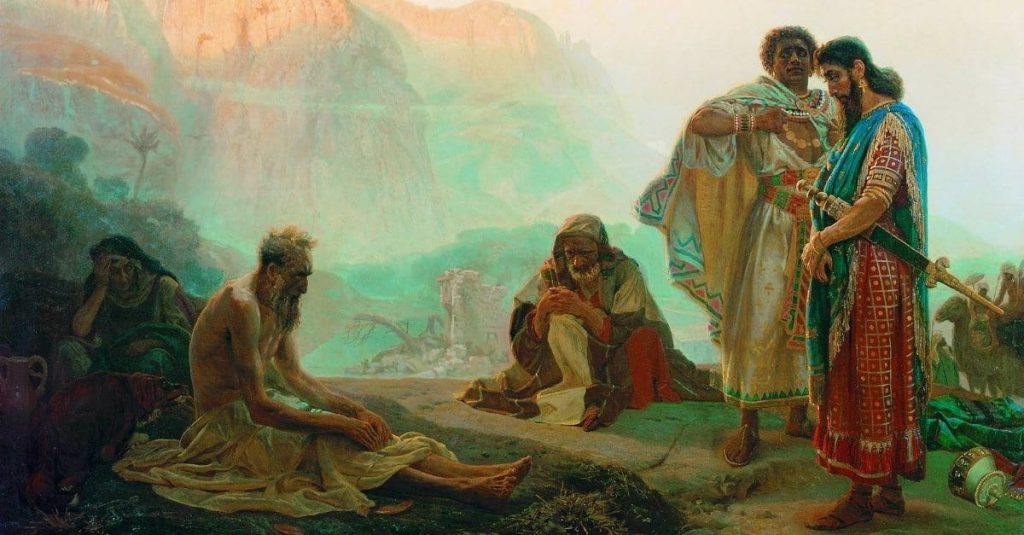

Three of Job’s friends, meanwhile, have gotten wind of what has happened to him and set out together to provide comfort. They are blown away by what they find:

“When they saw him from a distance, they could hardly recognize him; they began to weep aloud, and they tore their robes and sprinkled dust on their heads. Then they sat on the ground with him for seven days and seven nights. No one said a word to him because they saw how great his suffering was” (Job 2:12-13).

Years ago, when I was going through one of the hardest times in my life, a friend came to see me. We simultaneously pulled into the parking lot of the restaurant where we had agreed to meet.

As soon as he saw me, he began to cry.

My friend may have felt a bit awkward. It’s not always easy for guys to cry. Perhaps he imagined that he was going to say something profound. All I know is that I will never forget that moment. He didn’t need to say or do anything else. His tears were the greatest gift he could have given to me. They restored my hope.

When Job’s three friends show up, they get things just right. They sit down and say nothing.

In large part because of this story, sitting shiva is a cornerstone of the experience of grief in Judaism. Shiva is the Hebrew word for “seven.” To sit shiva, then, means to be present for seven days with a bereaved person, quietly providing a setting where that close friend or loved one can work through the initial waves of grief.

This dovetails with the apostle Paul’s gentle words in Romans 12:15: “Mourn with those who mourn.”

Notice what Paul doesn’t say.

He doesn’t advise his readers to tell a grieving person that everything’s going to be OK. Or to give them the contact information of a local grief therapy group. Or to provide a likely explanation for why this awful thing happened. Or tell them that since it’s been a few weeks, maybe they should stop crying. After all, people who trust God shouldn’t cry, right?

If only Job’s three friends had stayed quiet. But apparently they just can’t help themselves.

Just a few chapters into the book, they flat-out accuse Job of being the source of his own misery. When God shows up at the end, Job is vindicated. But his three friends are identified as candidates for Remedial Counseling Training. They hadn’t helped the man they came to comfort. They had only made his pain feel worse.

When people are asked to look back over their lives and identify what most helped them grow spiritually, one answer consistently rises to the top: suffering. God uses pain to accomplish incredible things. Which means our primary call isn’t to rush in and fix someone’s pain, or explain it, or try to change the subject.

Our call is to share that pain, perhaps by doing nothing more than shedding tears or sitting quietly nearby.

Where is God when life hurts? Until we’re all in the next world, we won’t be fully able to answer that question.

But in the meantime we can know how to answer a corollary question: Where should we be when life hurts?

We should be nearby, giving the gift of simply being present.