To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

Hollywood’s love affair with Indiana Jones launched an international passion for archeology.

Who wouldn’t want to crack open the door of a long-forgotten temple – unseen by human eyes for centuries – in order to search for priceless treasures? OK, maybe crack open the door of a long-forgotten temple without all the cobwebs and snakes and poison arrows.

College-level archeology classes exploded in popularity at the end of the 20th century, and many of the men and women who are currently digging into the past acknowledge that George Lucas’ films are what first ignited their interest in the field.

Real-life archeology, of course, rarely involves the kind of “loot and scoot” adventures we see on the screen.

Archeologists spend much of their time taking notes and taking pictures. They painstakingly work their way through piles of broken pottery. They are far more likely to find a few scraps of papyrus or a piece of bone than an amulet worn by a queen. We may consider contemporary graffiti a nuisance or even a desecration, but archeologists are always fascinated to see what people in ancient times scrawled on their walls.

One such graffito (that’s the singular of graffiti) from a wall in ancient Rome has attracted considerable attention.

In was discovered in 1857 when archeologists unearthed part of the imperial palace of Caligula, one of the most notorious of the early Roman emperors. Historians believe the property became a boarding school for the messenger boys of Roman nobles. It appears that one of the boys was doing what boys tend to do in every generation – pick on another kid.

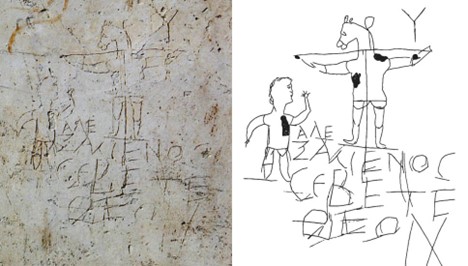

A photograph of the graffito appears in the left panel above, with a rendering of its simple lines on the right. Someone has drawn a crude picture of a man being crucified. Instead of a human head, the victim bears the head of an ass. A smaller figure stands to the left, with one arm extended toward the cross. Underneath, scrawled in crude Greek letters, are the words, “Alexamenos worships his God.”

No one knows the back story of this picture. But we can guess.

A boy named Alexamenos was a Christian. At least one other boy decided to mock him.

The graffito can be dated somewhere between the first and third centuries A.D. It’s well known that the pagans of the Roman Empire dismissed the worship of Jesus as absurd. Paul wrote to the church at Corinth (just after A.D. 50), “We preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles” (I Corinthians 1:23).

What made “Christ crucified” foolishness?

Crucifixion wasn’t just capital punishment. It was the most humiliating thing to which a human being might be subjected. Roman citizens, by law, could not be crucified. The cross was reserved for traitors and slaves. Depictions of this form of punishment were considered deeply objectionable. That’s why the cross didn’t begin to appear with regularity in Christian art until the sixth century.

Marcus Cornelius Fronto, a second century Roman orator, declared that “the religion of the Christians is foolish, inasmuch as they worship a crucified man, and even the instrument itself of his punishment.”

Pagans could not fathom the idea that someone who was nailed, naked and alone, to a couple of wooden planks was worthy of honor and respect. The cross was intended to subtract all honor and respect. On top of that, the suggestion that a divine being would come to earth and suffer ignominious defeat – and then be worshiped as the one who alone could defeat evil – was simply laughable.

So Alexamenos was jeered. Have fun with your Holy Ass god.

We need to understand that this was normal during the first centuries of the church. Jesus even warned his disciples that if he was going to be mistreated and misunderstood, they were also going to be mistreated and misunderstood (see John 16:1-4). That’s not what we would prefer, of course. But it’s part and parcel of being a follower of Jesus.

A strange idea, however, sometimes gains traction in places where Christianity, over time, becomes the majority religion.

It goes something like this: Jesus ought to be respected. In fact, he must be respected. Christians should never have to put up with ridicule. Those who mock Jesus should be held accountable.

The movement called “Dominion Theology” has captured the imagination of some American churchgoers. It’s not subtle. Our country must be “taken back” for Christ. Christianity shouldn’t be one among many options on the spiritual smorgasbord. The government should be reconstructed in such a way that Christianity alone is given religious entitlements. The Constitution might be useful, but only to a point. Why not treat it as merely a vehicle for implementing biblical principles?

Perhaps we should let Paul have the last word. A few sentences later in the same letter to the Corinthians he writes, “But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things—and the things that are not—to nullify the things that are” (I Corinthians 1:27-28).

Jesus never said, “I can’t wait for my followers to elect enough officials and pass enough laws to require their whole society to acknowledge me.”

Should we work and serve and pray as earnestly as we can to influence everyone we know to love God and love each other?

Of course.

But we should never be surprised that Jesus isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. Some people – perhaps many people – will always see him, as Paul puts it, as foolish, weak, shameful, and despised.

Nor should we be surprised if someone scrawls a graffito that says the very same things about us.