To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

Do all dogs go to heaven?

What we know for sure is that all dogs may go to church in St. Johnsbury, Vermont.

That’s where a wood carving artist named Stephen Huneck, after suffering a life-threatening illness in 1998, decided to build the Dog Chapel, a place of worship dedicated to his favorite canines.

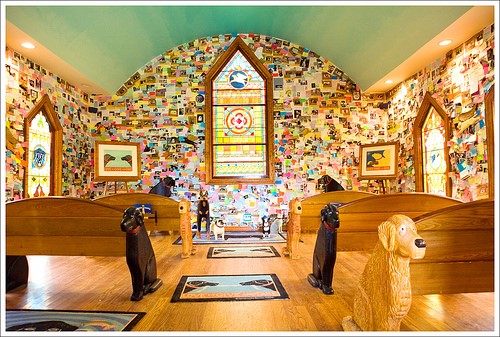

Carved wooden dogs line the pews. Dogs are featured in every stained-glass window. There are human-sized entryways as well as a small door crafted especially for mutts.

The walls are covered, from floor to ceiling, with notes and pictures that commemorate the cherished pets of chapel visitors. Many of them no doubt express the hope that an old friend with a wagging tail will be waiting to greet them in the next world.

The Dog Chapel has a great slogan: All Creeds, All Breeds – No Dogmas Allowed.

So what’s a dogma?

A dogma (from the Greek verb dokeo) is a principle or a teaching that is incontrovertibly true. According to certain religious authorities, it cannot be doubted. No matter what you happen to think or feel, a dogma simply must not be doubted or rejected.

Therein lies the current unpopularity of dogmas.

The spirit of our age is that being absolutely right about any religious idea is just flat-out wrong. In the spirit of the Dog Chapel: No dogmas allowed.

The problem with that statement, of course, is that it’s highly dogmatic. “There’s no such thing as absolute truth!” That seems like a bold and liberating declaration until you realize you just proposed an absolute truth.

In reality, Christian dogmas become exasperating when followers of Jesus become dogmatic about things that don’t really matter, at the expense of things that genuinely do.

Does it really matter whether someone has to go all the way under the water in order to be properly baptized? Or how many pairs of animals could fit onto Noah’s Ark? Or whether Christians should go to a theater to watch a movie, shop on Sundays, wear jeans to worship, or enjoy a glass of wine with dinner?

All too often, congregations have turned such peripheral issues into spiritual litmus tests – dogmas that determine who’s in and who’s out, and which behaviors merit God’s sternest disapproval.

Father Richard Rohr points out that there isn’t a single text in the four New Testament biographies of Jesus (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) where Jesus denies people access to God because of their sins or failures. He is unfailingly inclusive.

That’s not to say that Jesus is apathetic about human behavior. No one ever set the spiritual bar higher: “Therefore be perfect, even as your Father in heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48).

But Jesus’ expectations of Maximum Holiness are accompanied by the promise of Maximum Grace. And tellingly, he reserves his fiercest rebukes for those who would deny other people such grace, who would even slam heaven’s door in their faces. Ironically, those are the very people most in danger of losing their standing with God (see Matthew 23).

So is there a dogma we can all agree upon?

Rohr suggests it might be Jesus’ teaching that we should always pray for our enemies and always forgive those who hurt us.

What would church history look like if that had been at the heart of every congregation’s life?

There would be a lot fewer people saying that church has gone to the dogs.