To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

Throughout the month of August, we’re looking at Ecclesiastes, that strange and seemingly “modern” Old Testament book that depicts what happens when humanity searches for ultimate meaning apart from God.

Growing up in the 1950s, my brothers and I did what we assumed every other American boy was doing. We collected baseball cards.

At the local drugstore you could get five cards and one thin slab of gum for five cents.

The gum, which tasted good for about five minutes, was the invention of a 23-year-old accountant named Walter Deimer, who in 1928 worked for the Frank H. Fleer Company. Deimer was committed to creating something that would allow kids to blow awesome bubbles. He kept experimenting until he had produced a 300-pound, monstrous glop of sugar-based goo. The only food coloring available at Fleer at the time was pink, so that became the universal color for bubble gum.

Deimer named his invention Dubble Bubble. It would ultimately bring untold joy to both children and dentists.

Our dad, meanwhile, had taught us that not all baseball teams were created equal.

The New York Yankees, seemingly perennial World Series champions, were nothing less than the Evil Empire. Therefore we took revenge on the Yankees in the only way we knew how: by abusing the cards that depicted their best players.

I remember inserting Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, and Roger Maris cards into the spokes of my bike. The result was both an awesome sound when I rode down the street and serious wear and tear on the cards.

Take that, Yankee sluggers!

The joke, of course, was on us. Who knew that years later members of our own Baby Boom generation would lead the way in generating a nostalgia-driven classic card craze?

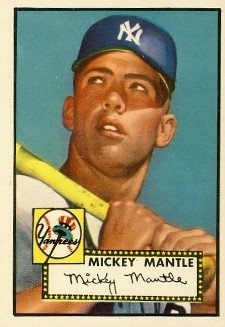

Mickey Mantle’s 1952 rookie card, pictured here and technically known as Topps 311, is widely considered the most popular baseball card of all time.

Topps had produced hundreds of thousands of them. But sales were disappointing in the early 50s, and storage space was limited. Therefore an entire barge of mint condition Topps baseball cards, including a mother lode of Mantle 311s, was unceremoniously dumped into a local river. That, of course, was ecologically irresponsible. It also contributed to the card’s rarity. And rare things sometimes become valuable.

A Mantle rookie card, if purchased in a five-pack at the drugstore, originally cost one penny. By 1978 a 311 in good shape was worth around $600. By the early 80s the price had jumped to $3,000. About 10 years ago, a Mantle 311 sold for $40,000.

Then things got crazy. In 2018, a 311 in flawless condition was auctioned off at $2.88 million.

Apparently the original owner of that card had had the good sense not to punish Mickey with his bike.

What’s going on here? How can a cheap piece of cardboard ascend to such Himalayan heights of value?

Mike Burkes, co-founder of the National Sports Collectors Convention, thinks he knows the answer: “To get the card back was to get childhood back. “

In The Last Boy: Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood, Jane Leavy proposes that two men – Mantle and Elvis Presley – came to represent America’s boundless hope and optimism of the 1950s. Both were ravaged by self-doubt. Both became addicts and died relatively young. Both remain the idols of millions of people – symbols of wistful yearning that we might somehow become innocent again, and as happy as little kids in a sad and dangerous world.

Where in the Bible do we find such a vision for reclaiming our innocence?

Incredibly, the answer is Ecclesiastes. The same book that compels us to stare into the abyss of Meaninglessness urges us to take joy in life’s simple pleasures.

The author writes in 2:24-25, “A person can do nothing better than to eat and drink and find their satisfaction in their own toil. This too, I see, is from the hand of God, for without him, who can eat or find enjoyment?” And in 3:12 we read, “I know that there is nothing better for people than to be happy and to do good while they live.”

Don’t worry. Be happy.

This feels light years away from wrestling with the heavy philosophical issues of why we’re here in the first place. It’s a preview of the “healthy hedonism” that pervades the rest of the book – the assurance that people who receive the love and grace of God can actually become reacquainted with the sense of wonder they used to feel when they were young.

We cannot start life over again, of course.

But Jesus puts another option on the table: We can be reborn.

Spiritual rebirth doesn’t change our DNA, erase our worst memories of high school, or undo decisions that keep us awake at night. But rebirth nonetheless brings wonderful gifts: new understanding, new power, and new hope. Being reborn is like operating the old hardware of our lives with new software.

Jesus was entirely serious when he said that unless we become like little children, we can’t really grasp what God is up to in this world.

By God’s grace we can gradually reclaim the trust we once knew as kids.

Even if we can’t undo life-altering childhood decisions such as, “I think I’ll be a Cubs fan.”