To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

Great musicians write killer songs.

One of history’s greatest musicians wrote a composition that almost “kills” those who are courageous enough to try to play it.

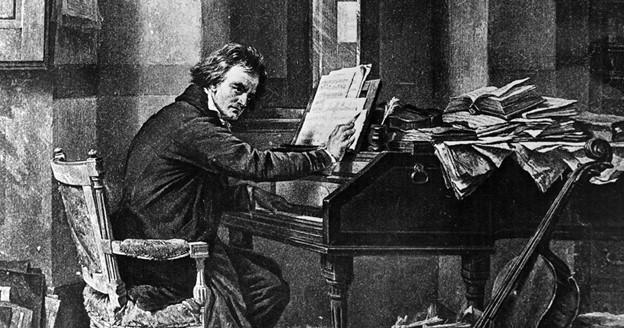

We’re talking about Ludvig van Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata, arguably the ultimate piano masterpiece from the man who almost singlehandedly defined the technical possibilities of the keyboard.

Beethoven wrote 32 piano sonatas. Sonata Pathetique (No. 8) and The Moonlight Sonata (No. 14) are his best known, and lie well within the range of moderately talented pianists. But the Hammerklavier (No. 29), which was published in 1818 during the last great compositional flourish of Beethoven’s life, is not for beginners.

Music historian and composer Robert Greenberg calls it “the big, gnarly, nasty knucklebuster.”

Hammerklavier is German for “hammer-keyboard,” which was Beethoven’s preferred name for the instrument the Italians called a piano-forte (literally, a “soft-loud”), which we today simply call a piano. During his lifetime, pianos were rapidly evolving from humble, fragile things (his playing style was so violent that, more than once, strings snapped right off the soundboard) into instruments that could mimic an entire orchestra.

Greenberg describes the 29th sonata as “a mega-sonata for future mega-pianos, pianos that didn’t even exist at the time.” Beethoven was trying to go as far as someone could possibly go, compelling the pianist’s hands to range up and down the keyboard at lightning speed, crossing over at odd angles, hovering over endless trills.

The fourth movement of the Hammerklavier is a fugue – a classic device where a musical subject is introduced in one “voice,” then repeated a number of times at higher and lower pitches, perhaps even in different keys. Critics have called Beethoven’s effort the fugue to end all fugues. Can the piece go faster? Then faster still? What if the fugue subject is suddenly introduced upside-down?

It’s little wonder that from the day it was published, the fourth movement of the Hammerklavier was considered virtually unplayable. It seemed to be an idealized composition, the technical demands of which raised the bar far beyond what was reasonable.

The Ukrainian-American pianist Valentina Lisitsa, fortunately, has shown herself equal to the task. When you can, take a few minutes to check out her extraordinary performance.

Let’s be honest: This composition is not what most of us would call beautiful or restful or joyful. It sounds more like the depiction of a colossal struggle.

And that would be a great way to describe Beethoven himself.

Greenberg suggests that while many of us might envy Beethoven’s gifts, not one of us should envy the German composer’s life. He had a harrowing childhood under the rod of a cruel, overbearing father. He became a “crotchety, touchy, irascible man, even on his best days.” He was not physically attractive, but was short, clumsy, and cursed with “the worst hair this side of the Bride of Frankenstein.” Beethoven was unlucky in love, angry, isolated, and lonely. He became obsessively paranoid to the point where some of his friends feared for his sanity.

And perhaps, in the end, he was in fact a little mad.

Worst of all, he gradually suffered the loss of the one thing a musician needs more than anything else: his hearing. By 1818, as he was finishing the Hammerklavier, he was completely deaf in his right ear and could only hear low frequencies in his left. But his genius was such that he could still sound out the right notes in his compositional imagination.

How did Beethoven respond to so much suffering?

Since he couldn’t post his troubles on social media, pour them out to a cognitive behavioral therapist, or appear as a guest on Jerry Springer, he translated his experiences into music. As Greenberg puts it, “he composed music that by some amazing alchemy universalized his problems and his solutions.”

That’s another way of saying that Beethoven’s compositions are expressions of his own colossal struggles. And he wrote in such a way to let us feel what he felt in those struggles.

The Hammerklavier Sonata represented a turning point in Beethoven’s spiritual and musical life. Its pounding chords and roaring cadences seem to be asking – more like demanding – answers to some very hard questions:

God, who are you, and why do you behave the way you do? If this is your world, why is there so much disorder? What greater good can possibly be served by taking away a musician’s hearing?

Critics agree that Beethoven’s music, although often agonizing, inevitably lands in the same place: “There is hope.” When the last notes of the Hammerklavier are played, we sense that there is beauty, complexity, and an underlying order to the cosmos, even in the midst of our struggles.

Beethoven would never have been caught dead in church.

But he exuded the kind of awe that we encounter in Psalm 8:1: “O Lord, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth.”

As for why one of the world’s greatest composers should suffer the loss of his hearing, we can only affirm that it accomplished something that might otherwise have never happened: the creation of some of the most stirring and hopeful music the world has ever heard.

And it just may be that our own struggles are accomplishing equally beautiful things.