To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

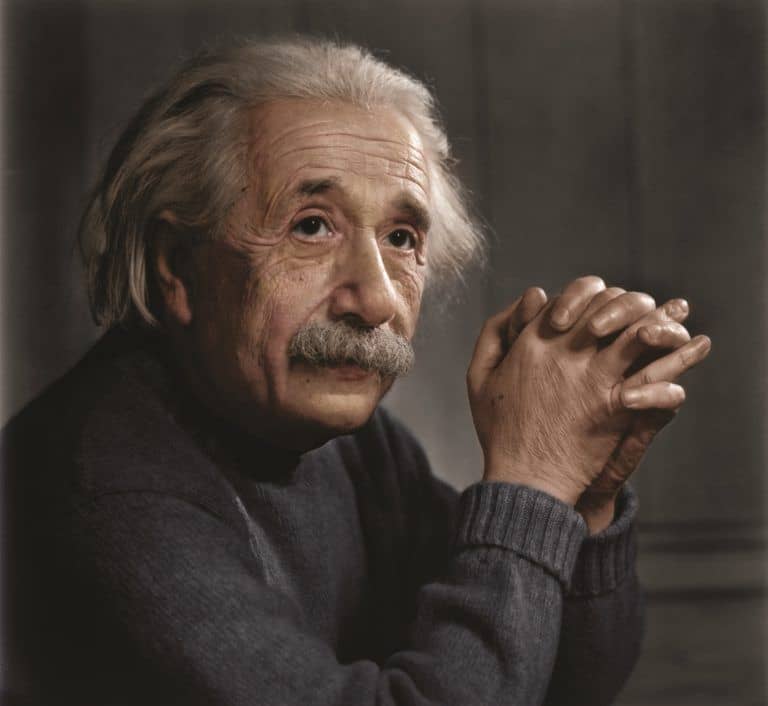

During the course of a single year (1905), a young man named Albert Einstein submitted several papers to a German physics journal.

This was surprising, since Einstein had no scientific pedigree, no university affiliation, and no laboratory to conduct experiments.

He was employed at the time in the Swiss national patent office in Bern, where he was a technical examiner third class. He had recently sought a promotion to technical examiner second class, but his application had been rejected.

Social historian Bill Bryson summarizes the impact of three of the papers that Einstein submitted to Annalen der Physik:

“The first won its author a Nobel Prize and explained the nature of light (and also helped to make television possible, among other things). The second provided proof that atoms do exist – a fact that had, surprisingly, been in some doubt.

“The third merely changed the world.”

Einstein’s special theory of relativity, the subject of the third paper, transformed humanity’s understanding of the cosmos. It was an extraordinary article in that it had no footnotes, no citations, no previous sources, and contained virtually no math.

It’s almost as if he “had reached the conclusions by pure thought, unaided, without listening to the opinions of others,” writes historian C.P. Snow. “To a surprisingly large extent, that is precisely what he had done.”

As Einstein became internationally famous, the New York Times decided to run a story.

Unfortunately they sent their golf correspondent, Henry Crouch, to do the interview.

Crouch knew considerably more about fairways and bunkers than theoretical physics. The story was laughably inaccurate, and included the journalist’s conjecture that only 12 people “in all the world could comprehend” the theory of relativity.

With the passing of time, that number got smaller and smaller in the public imagination.

Bryson recounts: “When a journalist asked the British astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington if it was true that he was one of only three people in the world who could understand Einstein’s relativity theories, Eddington considered deeply for a moment and replied, ‘I am trying to think who the third person is.’”

The theory of relativity is so remarkable and so far-reaching it just has to be impossible for ordinary people to comprehend. Right?

Something similar happens when ordinary people try to wrap their heads around the essence of the Christian message.

There are so many Bible verses. And so many theories about what really happened on the cross. And so many different churches with all their different views of baptism, worship, and sacred rituals.

Who can make sense of it all?

Karl Barth, one of the 20th century’s most celebrated theologians – who also happened to be a citizen of Switzerland – was a guest speaker at the University of Chicago in 1962. During the closing Q&A time, a student asked Barth if he could summarize his whole life’s work of theological reflection in a single sentence.

Barth replied, “Yes, I can. In the words of a song I learned at my mother’s knee: Jesus loves me, this I know, for the Bible tells me so.”

We may think that only the brightest people on earth can comprehend the meaning of the universe.

But you don’t have to be an Einstein to grasp what really matters.

God has ensured that even a child can get it right.