Even before the final shots of the Civil War, another great conflict had broken out between the North and the South.

It was the battle of the cemeteries.

Before 1864, there was no national cemetery in the United States. Few people imagined the need for such a place. But the monumental struggle between the Union and the Confederacy cost an estimated 650,000 lives – more than the total casualties from all other American wars combined, even to the present day. As the bodies of young men literally began to pile up, officials began to wonder where they could possibly be buried.

Union Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs had an idea – one that was stoked by personal bitterness.

Why not bury Northern soldiers on the land that was owned by the most painful thorn in the Union’s side – General Robert E. Lee?

Meigs and Lee were both Southerners. They had been classmates at West Point, and had worked closely together as military engineers. But when the Confederacy came into existence in 1861, Lee had resigned his commission with the U.S. Army so he could serve his native state of Virginia. Meigs remained loyal to the Union.

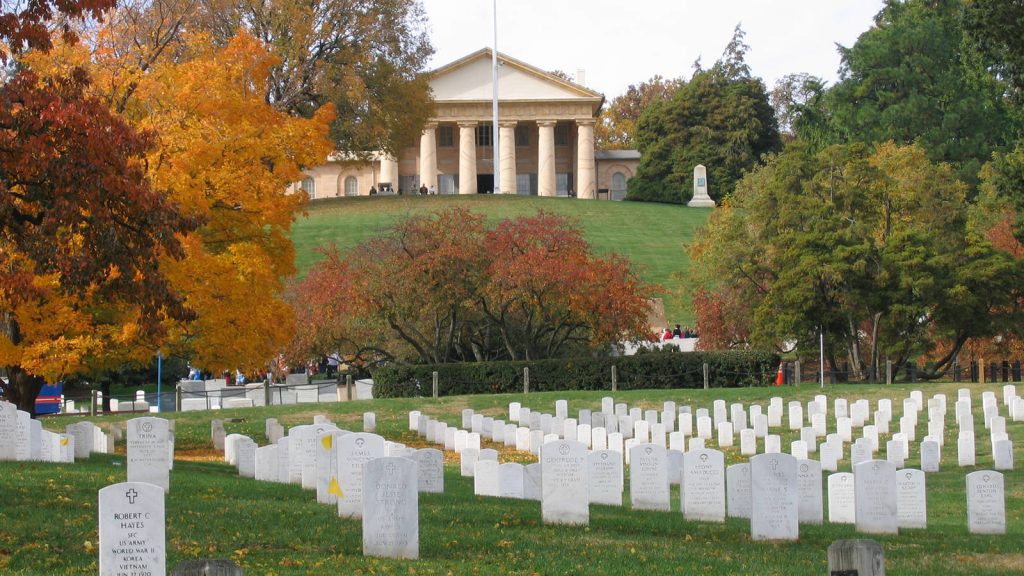

Lee and his family had lived for 30 years in a mansion high atop a hill just across the Potomac River from Washington D.C. He had abandoned his beautiful Arlington Estate at the start of the war, and Union forces immediately seized it so Rebel troops couldn’t mount cannons there.

Meigs recommended that Northern war dead be buried so close to Lee’s house that he could never return.

By the end of the war, there were 7,000 fresh graves in what would eventually become known as Arlington National Cemetery. One of those buried was Meigs’ own son. Moved by deep anger, Meigs personally supervised the interment of 26 soldiers in Mary Lee’s cherished rose garden – a decision that broke her heart. It seemed unjust to her that a place she had loved was now “surrounded by the graves of those who aided to bring all this ruin on the children and the country.”

By the end of the war, funds were being raised to establish four other national cemeteries, including one at Gettysburg.

Hard feelings prevailed. No Confederate bodies were allowed to be buried at these sacred sites. Nor were African-Americans, including those who had fought and died for the Union cause.

In the South, meanwhile, societies of women – many of them war widows – rallied to honor their own dead. During the war, three times as many Confederates had died as their Northern counterparts. Reburial teams traveled to the sites of the biggest battles, where hundreds and even thousands of men had been hastily committed to the ground. Many of them were now impossible to identify.

Strong passions swept the newly reunited country to “remember those who had made the ultimate sacrifice.” On May 1, 1865, a crowd of about 10,000 people – the majority of them freed slaves – gathered near Charleston, South Carolina to rebury and honor approximately 250 Union soldiers who had died in prison camps nearby.

States began to establish their own days of remembrance. They were usually in the spring, when flowers would be fully in bloom and Easter might provide reminders of hope. By the 1870s, a movement had begun to designate May 30 as Decoration Day. It was chosen for the simple reason that no significant Civil War battle had been fought on that date.

By the early 20th century, Decoration Day had morphed into an opportunity to honor the dead from every American conflict. In 1948, President Truman finally declared that national cemeteries should be racially integrated. The newly identified Memorial Day – designated as the fourth Monday of May – became an official holiday in 1971.

Yet even after 156 years, resentments linger.

Many of the Confederate monuments at the center of today’s fierce public debates were erected by Southern societies who felt their dead fathers and brothers had been snubbed and dishonored by the national cemeteries. To this day, gravesites are where some people are still fighting the Civil War.

Should Americans try to erase history?

We can never wipe away the reality of historical events. But there is something we can do: With the help of God’s Spirit, we can endeavor to eliminate whatever traces of bitterness, prejudice, and rancor might still be festering in our own hearts.

In April 1866, just one year after the guns of the Civil War fell silent, a group of women from Mississippi traveled together to the Tennessee border, where tens of thousands of Yankees and Confederates had perished at the Battle of Shiloh in 1862.

They placed flowers atop the Confederate mass cemetery. Those graves had been lovingly tended for the previous four years.

The Union graves, however – since they were far away from the nearest Northern state – had fallen into comparative ruin.

The Southern women decided to place flowers on those graves, too.

There is still so much work to do. And so much healing that still needs to happen. But we can help turn the tide.

All it takes to begin is a single act of love.