To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

In the movies, when one gentleman offends or insults another, they immediately “throw down.”

I challenge you to a duel! And just like that, out come the swords or pistols or some other means of settling things, usually with fatal consequences.

But that’s not how dueling happened in real life. According to historian Scott Mitchell, “A duel was the final part in what was an elaborate and ritualized negotiation between gentleman called an ‘affair of honor.’”

Over the centuries, a set of rules had been developed to prevent the firing of guns or the slashing of swords. These regulations were intended to slow things down, to let the parties cool off, to give them time to resolve their differences – all in the hope that everyone might somehow emerge from the conflict with their honor intact.

The rules came to be called the Code Duello. It was frequently able to prevent disaster.

In 1791, for instance, the Secretary of the Treasury in George Washington’s cabinet was accused of a crime. James Monroe, a future two-term president, accused the secretary of enriching himself with government funds.

The treasury secretary declared his innocence. He then shared a secret with Monroe. The perception of financial irregularities was due to a personal matter. He was in fact guilty of an affair with a woman named Maria Reynolds, who with her husband had been blackmailing the secretary for more than a year. He proved it by showing Monroe a stack of letters.

Monroe vowed that he would never let those letters see the light of day. The secretary was relieved. He would not be publicly humiliated.

Unfortunately, Monroe hedged on his promise. He revealed the letters to one other person – to Thomas Jefferson, who would also turn out to be a two-term president – and who five years later recognized that the Reynolds Affair would be the perfect way to destroy the life and career of the treasury secretary. After Jefferson leaked the letters, the secretary savagely turned on Monroe. You betrayed me. I demand satisfaction.

Monroe was defiant. I did nothing of the kind. I demand your apology, sir.

The rancor escalated. The pair exchanged angry letters and called each other vile names. The dispute seemed headed for violence.

That’s when the Code Duello provided an escape. According to the traditional rules, each party should be represented by a friend, who is called the “second.” One of the roles of the second is to help tone down the rhetoric. In this case, Monroe’s second urged him to tear up his angriest letters and adopt a more conciliatory tone. He also calmed down the secretary. In the end, the two men were able to find the grace to apologize and move forward.

That’s how things were supposed to work.

If peaceful negotiations had failed, and the two parties had resolved to fire at each other, Code Duello specified that guns with rifled barrels could not be used. Mitchell points out that dueling pistols had smooth bore barrels, which were highly inaccurate at the distance of 30 feet. The bullets rattled around in the chamber so much that there was actually little chance of predicting where they might end up.

That’s because the goal, in the end, wasn’t really to kill the other party. It was to save face by showing that you were willing to risk your own life for your beliefs.

Says Mitchell, “It was enough that both parties showed up, ready to die.” Despite Hollywood’s dramatic depictions, that rarely happened. Combatants frequently missed their targets on purpose. Only about one in five duels proved fatal.

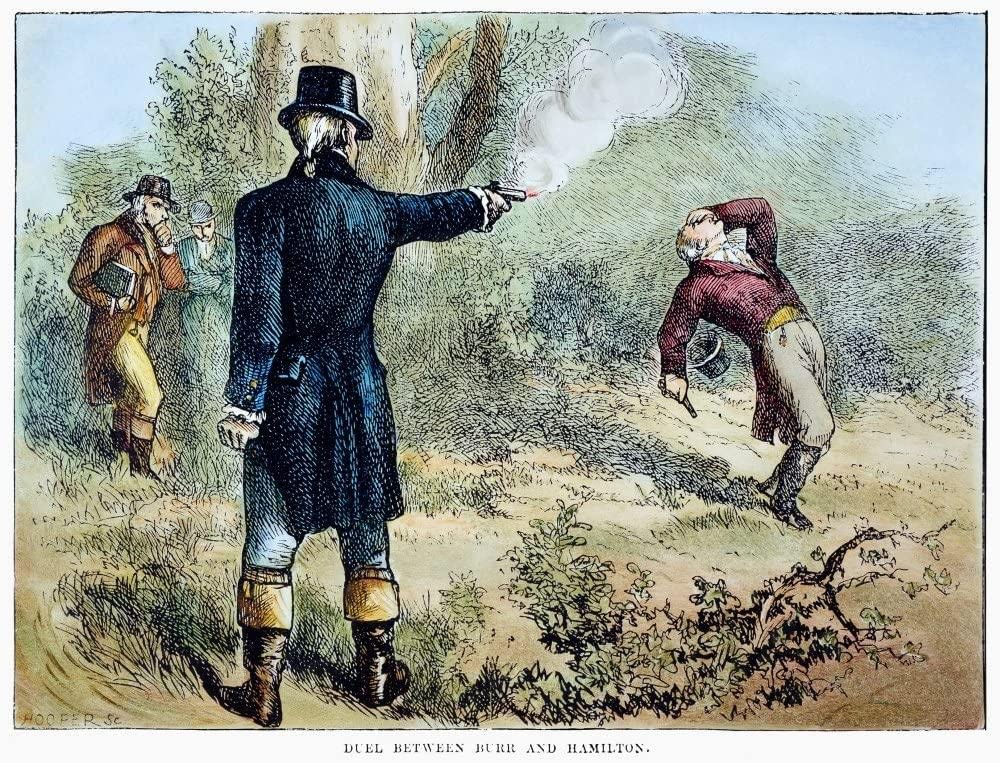

In the case of Monroe and the Secretary of the Treasury, neither had to draw a pistol. And who was Monroe’s skillful second, the one who acted as the voice of reason? It was Aaron Burr. And who was that particular secretary? It was Alexander Hamilton, whom Burr – in the irony of all ironies – would ultimately kill in the most famous duel in American history in 1804.

Burr is often remembered as the bad guy. But by all accounts, he was a peaceful and charming human being. Hamilton, on the other hand – who was absolutely brilliant and arguably one of the most competent of all the Founders – might best be described as a petulant, hotheaded, unforgiving jerk. Perhaps he was irritated because he suspected that the musical that would one day be written about his life would mostly be hip-hop.

Hamilton found it hard to get along with others. He was offended by even the slightest criticisms, and was challenged to 11 duels over the course of his life.

He enjoyed lobbing public insults, and mocked Burr openly for something like 15 years. The latter finally said, “You’d better take that back.” Hamilton wouldn’t budge, and the two ended up facing each other on New Jersey’s Weehawken Island early on a July morning.

Is there something like the Code Duello in the New Testament?

The answer is No. The reason is that Jesus subverted the entire premise on which the Code is based.

Someone hurt me. My honor and reputation are at stake. I demand satisfaction – either a full apology, proving that I’m in the right, or a chance to reclaim my honor.

But Jesus said, in so many words, that honor is for the birds. All it does is drag us down into the quicksand of pride. Has somebody hurt you? Jesus says that it’s your responsibility to go that person and try everything you can to make things right (Matthew 18:15-17). Have you hurt somebody else? Jesus says that it’s your responsibility to go to that person and try everything you can to make things right (Matthew 5:25-26).

No matter what the circumstance, you go first. Whether you feel the hurt or have caused the hurt, you take the lead. When it comes to conflict, Jesus says that you are always in the driver’s seat. He will provide the grace and power you will need to become a non-anxious, healing presence. No other prominent teacher has ever said such a thing.

Most of us, of course, aren’t very good at being a non-anxious, healing presence, especially when we feel humiliated or disrespected. But practice will help us grow.

And most of us will have the chance, sooner or later, to serve as somebody else’s “second” – to come alongside a friend or family member or co-worker and say, “I know you feel hurt and angry right now, but let’s try to figure out how to get on the solution side of this conflict.”

This is where being a disciple is not for cowards. You may find yourself simmering, “But I know I’m in the right. I deserve an apology. Why shouldn’t I wait for one?”

The answer is that you might be waiting for a very long time.

In this broken world, you can hold out for being right or you can choose to be loving. Choose to be loving. You can insist on reclaiming your honor, right here and right now, or you can humbly trust that God will make things right in the end. Choose to be humble.

And every time you look down at Alexander Hamilton’s face on the 10-dollar bill, just remember:

You don’t have to fight somebody to be a winner in God’s eyes.