To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

Bob Ebeling was tormented by guilt for 30 years.

Ebeling was an engineer for Morton Thiokol, the contractor that built the solid rocket boosters for NASA’s space shuttles.

On the night of January 27, 1986, Ebeling contacted Allan McDonald, Morton Thiokol’s senior leader at Cape Canaveral, where the shuttle Challenger was scheduled for launch the next morning. He was convinced the launch should be scrubbed.

It was going to be 18 degrees overnight – exceedingly cold for Florida, even in the dead of winter. Ebeling thought the chill might damage the rubber O-rings that prevented the escape of hot gasses from the boosters.

Morton Thiokol had never tested for launch conditions below 53 degrees. It seemed insane to give Challenger the green light.

NASA’s leaders, unfortunately, had come down with a serious case of “Go Fever.” The flight had already been delayed on multiple occasions. The public was paying close attention, especially since schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe was one of the astronauts.

NASA insisted on the launch. McDonald was stunned. “This was the first time that NASA personnel ever challenged a recommendation that was made that said it was unsafe to fly. For some strange reason, we found ourselves being challenged to prove quantitatively that it would definitely fail, and we couldn’t do that.”

When asked to sign off on the decision to launch, McDonald refused. His boss signed instead.

Bob Ebeling trudged home that night, feeling devastated. “It’s going to blow up,” he said to his wife Darlene.

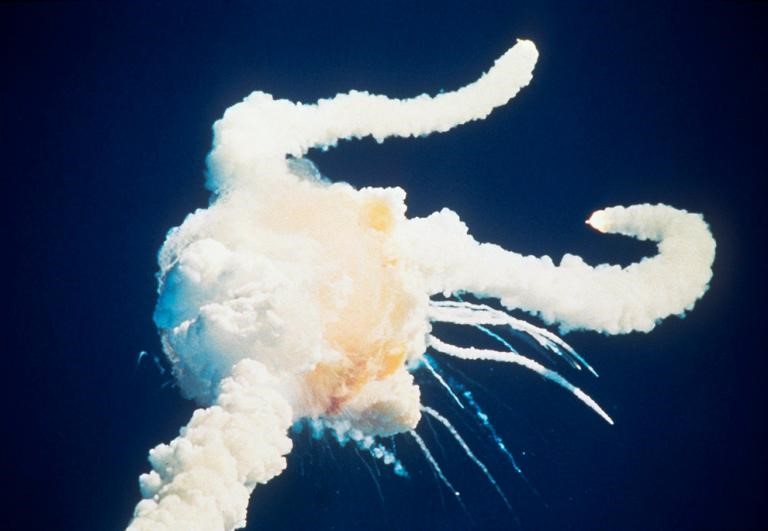

Seventy-three seconds into the launch the following morning, the O-rings failed. Challenger and its seven astronauts were lost. Sitting in a crowded conference room, watching the launch on a large screen, Ebeling at first trembled and then wailed with rage and sorrow.

He spent the next three decades haunted by the thought that he could have done more. He should have done more.

In a January 2016 interview that marked the 30th anniversary of the disaster, he lamented to NPR reporter Howard Berkes: “That was one of the mistakes God made. He shouldn’t have picked me for that job. But next time I talk to him, I’m gonna ask him, ‘Why me? You picked a loser.’ “

What Ebeling never saw coming was the avalanche of letters that poured forth from NPR listeners who had heard the interview.

One of them was written by Jim Sides, an engineer from Jacksonville, NC. “When I heard he carried a burden of guilt for 30 years, it broke my heart. And I just sat there in the car in the parking lot and cried.”

In his letter Sides pointed out that the Challenger disaster had become a celebrated case study in ethical decision-making for engineers everywhere. “You and your colleagues did all that you could do,” he assured Ebeling.

Sides also insisted that Ebeling was wrong about God. “God didn’t pick a loser,” he says. “He picked Bob Ebeling.”

The greatest surprise was a note that came from NASA itself – the first time he had ever heard from the space agency. NASA’s statement declared that the Challenger crew members were honored by the reminder to “listen to those like Mr. Ebeling who have the courage to speak up so that our astronauts can safely carry out their missions.”

Overwhelmed by the graciousness of such letters, Bob Ebeling told his family he was finally beginning to experience peace of mind. A few days later he lapsed into a coma. A few weeks after that he left this world at age 89.

In the case of Challenger, the very people who were supposed to know what was going on did in fact know what was going on, and accurately predicted what would happen next. It’s hard to be the dissenting voice, however, when a leader gets Go Fever. It’s hard to take a stand. Politics, ego needs, and the pressure to just go along with the consensus can feel crushing.

Ebeling explained in his NPR interview that it was his engineering background that prompted him to speak up. “Somebody should tell the truth,” he said.

But you don’t have to be an engineer to tell the truth.

Wherever you are – at work, at home, in your community, at a town hall meeting – the need of the hour is courage.

Do your best thinking. Remember to be humble. Choose to speak up – even if you’re not sure how others might respond.

Let your voice be heard.