To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

What language did Jesus speak?

For Bible scholars, that’s always been an interesting question.

We know that Judea in the first century was a tri-lingual culture. Hebrew was the “official” language of Israel – the mother-tongue that would be heard in the synagogue and in the prayers of God’s people.

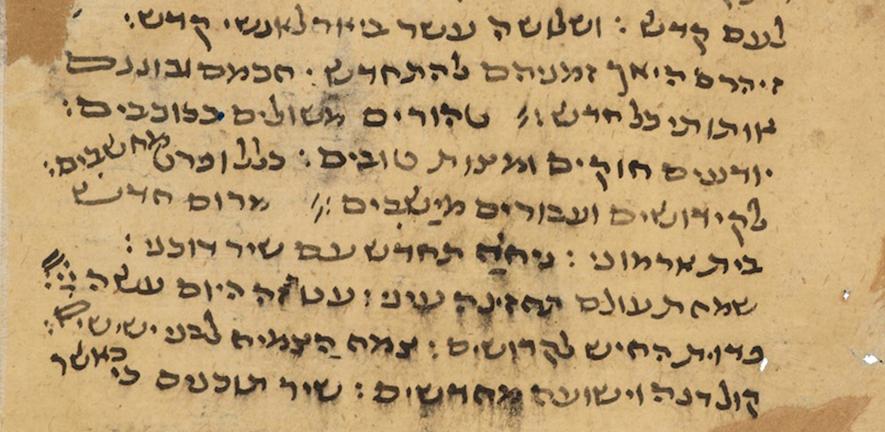

Aramaic – which looks and sounds a lot like Hebrew (see above) – was the dominant language of the Levant, the eastern Mediterranean region that included the historic areas of Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan. A Syrian trader who spoke Aramaic could do business in any of those places without having to master the local tongues.

Greek was the truly international language. It provided a common linguistic foundation for commerce and culture across the entire Mediterranean world – all the way from Gibraltar to Persia (present-day Iran). To add one more layer, Latin was the language spoken by the Romans, those ruthless people who had conquered the entire Greek-speaking world. The people of Israel had little desire to learn Latin.

Historians generally agree that most residents of Jerusalem during New Testament times would have been fluent in Aramaic and Hebrew, and probably knew some Greek. An educated person would have been able to shift from one language to another as the circumstances warranted.

Americans – we who complain about how hard it is to master a few bits of conversational Spanish, and wonder why everyone in the rest of the world doesn’t speak English – should feel profound respect for the people of ancient Israel. They were far more linguistically sophisticated than most of us.

So, what about Jesus?

The four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) were all written in Greek. That ensured that the details of his life might reach the widest possible audience. One of the strongest clues that Jesus spoke Aramaic on an everyday basis is the handful of Aramaic words and phrases that appear to be specially preserved in the Gospel texts.

There’s Amen – a word that has somehow retained its original meaning after thousands of years, not to mention jumping from one hemisphere to another.

There’s Abba, the Aramaic word for “pappy” or “daddy,” which Jesus daringly uses to address God Almighty in the Lord’s Prayer. And Hosanna, which roughly means, “Lord, save us!” (Mark 11:9), the word shouted by the crowds as Jesus enters Jerusalem just before his death.

The fourth Gospel rolls out the Aramaic word rabbouni (“teacher”) in John 20:16. That’s how Mary Magdalene addresses Jesus at the moment she encounters him near the empty tomb.

He says ephphatha (“be opened!”) while touching the ears of a deaf man in Mark 7:34. And to the young girl that he dramatically brings back from the dead, Jesus says talitha cum, a tender phrase which we can translate, “Wake up, sweetheart!” (Mark 5:41).

But the most poignant Aramaic expression in the Gospels is Eli, eli, lema sabachthani, which means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46). Those were among the famous last words that Jesus cried out on the cross.

It is impossible to overstate their power. Everyone who heard that cry, with the probable exception of the Roman soldiers who were actually crucifying Jesus, knew that it was the opening salvo of Psalm 22, where David the King shrieks in pain in the midst of suffering and loss.

Tim Keller, in his book King’s Cross, points out that as Jesus is dying he doesn’t scream, “My friends, my friends,” or “My head, my head.” He shouts, “My God, my God!” This is the language of intimacy.

Think of the way we might say, “That’s my Jennifer,” or “That’s my boy.” Keller writes: “If after a service some Sunday morning one of the members of my church comes to me and says, ‘I never want to see you or talk to you again,’ I will feel pretty bad. But if today my wife comes up to me and says, ‘I never want to see you or talk to you again,’ that’s [overwhelmingly] worse. The longer the love, the deeper the love, the greater the torment of loss.”

Think about the fact that “this forsakenness, this loss, was between the Father and the Son, who had loved each other from all eternity. This love was infinitely long, absolutely perfect, and Jesus was losing it… Jesus, the Maker of the world, was being unmade. Why? Jesus was experiencing our judgment day.”

A special word was even coined to express such pain. It’s “excruciating” – which literally means, “out of the cross.”

So why would the Messiah, if he really were at the heart of God’s will, ever have to suffer like this?

Here’s what we know:

If you have ever felt utterly abandoned; if you’ve ever been betrayed by someone who once promised a never-ending love; if you’ve ever been cut off from the health and the hope that used to sustain you – then you can know that the One to whom you are entrusting yourself today knows how you feel.

And he alone knows how to make you whole.

No matter what language we speak, that is arguably the most transforming word of assurance we can possibly hear.