To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

Mark Twain cherished no love for Christian missionaries.

In 1872, the famous author and satirist declared, “Hawaiians enjoyed an idyllic life before the missionaries braved a thousand privations to come and make them permanently miserable by telling them how beautiful and blissful a place heaven is, and how nearly impossible it is to get there.”

By the middle of the 20th century, Twain’s opinion was echoed by countless others. At the top of the list were sociologists who blamed religious outsiders for shamelessly imposing Western values and hangups on indigenous cultures.

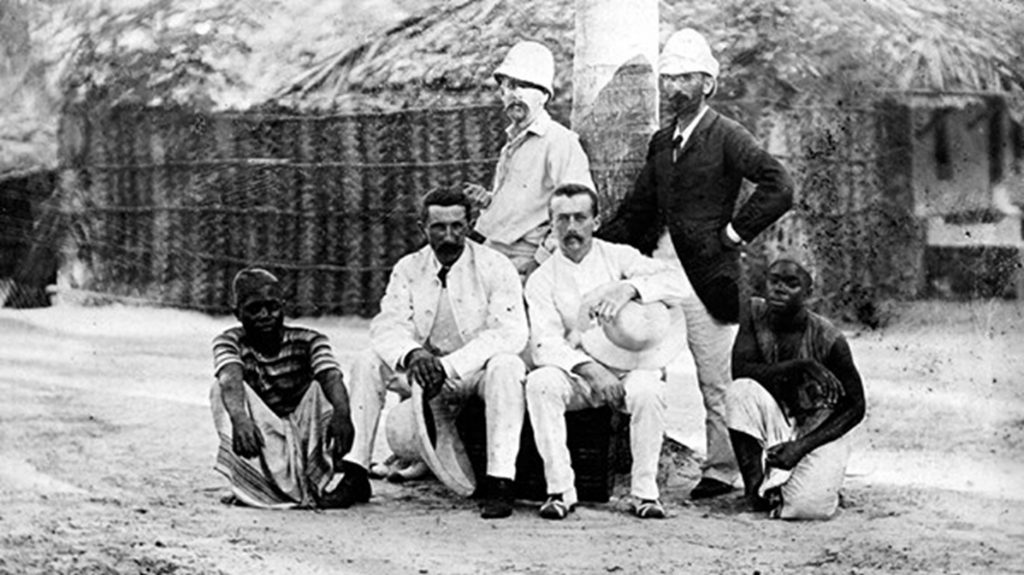

Whereas the 1800s used to be celebrated as the golden age of the Christian missionary movement, those same men and women are now generally seen as the exporters of the worst aspects of colonialism.

They may have thought they were bringing God’s good news to the rest of the world. But instead – so the charge goes – they merely frustrated the initiatives of the local people, stripped them of their wealth and resources, and corrupted the wisdom and beauty of traditional cultures by insisting on the superiority of their own ideas.

In his book How the West Won, the late sociologist Rodney Stark begs to differ.

Stark acknowledges that cricket – which the British introduced to every nation in their Empire – is perhaps not the greatest game on planet Earth. And Coca-Cola is surely not the most worthy Western export.

But the world seems to be a much better place because Western outsiders insisted on ending female foot-binding, the stoning to death of rape victims because of their “adultery,” and the practice of sati, where widows in India were compelled to burn themselves alive on their husbands’ funeral pyres.

All of those initiatives were spearheaded by Christian missionaries.

Mission workers brought far more than sermons and religious rituals. They exported medicine, education, and hope. Moreover, they often rallied to the defense of the people they were serving, protecting them from colonial officials and Western church governance. It’s well known, for instance, that the Catholic church occasionally threw Jesuit missionaries out of particular nations for the “crime” of advocating for the just treatment of locals.

Stark suggests that an appropriate way to evaluate the work of Jesus’ followers is by applying Jesus’ own standard: “You will know them by their fruits” (Matthew 7:20).

In that regard, missionary efforts that are more than a century old are still yielding a remarkable harvest.

In a 2012 article published in the American Political Science Review, Baylor research professor Robert D. Woodberry, summarizing 14 years of research, made the startling claim that Protestant mission workers can take a generous portion of the credit for the rise and stability of democracies in the non-Western world. Its eye-opening title was “The Missionary Roots of Liberal Democracy.”

According to his research, the greater the number of mission workers for every 10,000 people in a local population in 1923, the higher the probability that nation is now characterized by a stable democracy.

Woodberry examined 50 other factors that might have influenced the positive health of Developing World countries, including GDP and whether that nation was at one time a British colony. The so-called “Missionary Effect” surpassed them all.

That thesis runs so counter to the prevailing opinions of sociologists – that missionaries are the cause of the world’s woes, not an antidote to them – that Woodberry’s article was subjected to a storm of pre-publication criticism. He was compelled to turn over his notes and data so others could test and retest the validity of his conclusions.

The result was grudging acknowledgement. Then applause. Then came four major awards, including the prestigious Luebbert Article Award for superior research in the realm of comparative politics.

Woodberry points out that missionaries were “a crucial catalyst initiating the development and spread of religious liberty, mass education, mass printing, newspapers, voluntary organizations, and colonial reforms that made stable democracy more likely.”

If we zero in on just one realm – medicine – the numbers tell the story.

By 1910, Christian mission agencies had established 111 medical schools, more than 1,000 dispensaries, and 576 hospitals in non-Western nations. They had recruited, trained, and released thousands of local doctors and nurses. Woodberry reports that the higher the number of missionaries per 1,000 local residents in 1923, the lower the infant mortality in 2000 – a determining factor nine times as large as current GDP.

In other words, the presence of missionaries a century ago is positively correlated with higher life expectancy today.

Rodney Stark asks whether that should really be labeled as “cultural imperialism.”

“Then so be it,” he replies.

Sometimes, in our own churches, we hear mumbled apologies that our culturally out-of-touch great-grandparents were so obsessed with spreading the Good News that they bent over backwards to send missionaries to every corner of the world.

Praise God that they did.

And that we can know them by their fruits.