It is difficult to overstate how unpleasant it was to live in a city in the ancient Mediterranean world.

As historian Rodney Stark documents in his book The Triumph of Christianity, the earliest generations of Jesus’ followers tended to live and serve in urban areas like Antioch, Ephesus, Corinth and Philippi. These places were more crowded, crime-infested, and disease-ridden than any metropolitan district we can imagine today.

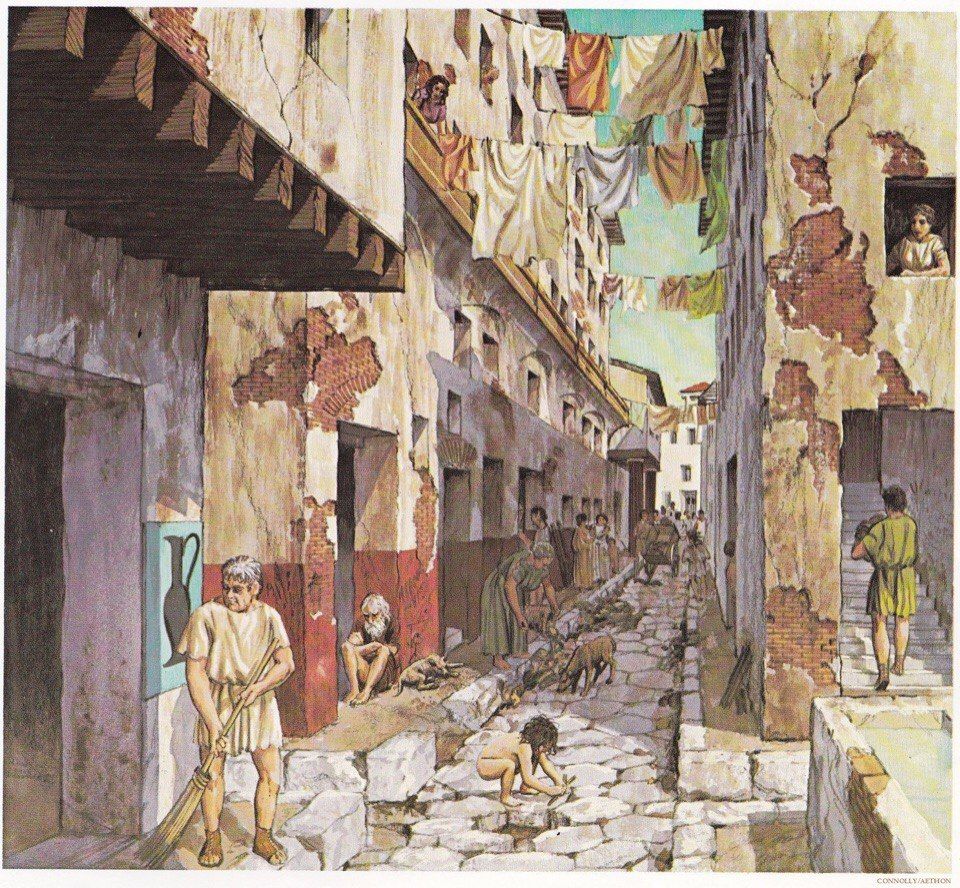

Ancient cities had relatively small populations. Most did not exceed 50,000 residents. But they were squeezed into extraordinarily small tracts of land.

It is estimated that first century Rome somehow crammed 302 people onto each acre. By comparison, Manhattan currently has 100 people per acre – and many of those live hundreds of feet above the street.

Tenements were squeezed impossibly close together and were built of shabby materials. Streets were sometimes nothing more than mere footpaths. Enterprising masons kept adding additional stories, but most buildings could not support the extra weight. Residents lived in constant fear of structural “pancaking.” Since open flames and charcoal grills were the only means by which to cook food, devastating fires in a multi-story building were always a threat. There were no chimneys, no ventilation, and no central heating.

Soap had not yet been invented. Sanitary sewers were a luxury reserved for the rich. Streets overflowed with garbage, filth, and the corpses of people and animals alike.

In commenting on the stench, Stark observes, “No wonder everyone was so fond of incense.”

It was dangerous to go out at night. Pickpockets, muggers, and even murderers for hire roamed the streets. Greco-Roman urban areas were far more dangerous than modern cities. One Roman observer wrote that if a wealthy person went out for dinner, he would be a fool if he didn’t first update his will.

Worst of all was the incidence of disease. Chronic health problems abounded. Most adults did not live to see their 35th birthday. In the pre-fingerprinting era, people were reliably identified by their scars and disfigurements.

Plagues arrived with terrifying regularity. A devastating epidemic swept through Rome beginning in A.D. 165. Historians suggest this may have been the first appearance of smallpox in Italy. Up to one-third of the population died over the next 15 years, including Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

No one knew what to do. No one knew how to help. Doctors, including the famous Roman physician Galen, fled the city. As soon as a family member showed signs of illness, that person was often abandoned on the streets to die alone.

Prayers to the pagan gods were considered ineffectual. Besides, there was no Roman god or goddess whose job was to offer compassion.

Mercy, in fact, was considered not a virtue but a pathological character flaw. Roman philosophers deemed it wrong to help the sick and dying. It distorted cosmic justice. “These losers obviously deserve what’s happening to them.” Pity was labeled a sign of weakness.

This was the nature of urban life when the Jesus Movement began to spread, slowly but surely, around the Mediterranean world.

In the midst of misery, Christians stood out from the crowd. They recalled that Jesus said that whenever we serve the sick and distressed, we are actually serving him (Matthew 25:31-46). God is a merciful God. Just as he has showered mercy upon us, we are called to shower mercy upon others.

And not just upon “our own people.”

What stunned the Romans is that when the plagues hit the city, Christians stayed behind to take care of strangers. They ministered to those abandoned in the streets, whose own family members had run for the hills. They fed them, nursed them, and provided a human face for them to look into as they died – a face that reflected the face of a God who actually said he loved them.

Did Christians also die from the plague? Absolutely. But historians estimate that their hands-on care saved more than 60% of those who would otherwise have been lost.

The upshot is that the Christian movement became famous not for theological wrangling or culture wars or somebody taking a stand on this issue or that. Myriads of people were drawn to Jesus because of the mercy displayed by his followers.

It’s likely that most people you will meet today will look nice, smell nice, and act nice. If you ask how they’re doing they’ll probably say, “Fine, thanks.”

But many of the people you will meet today will not be doing fine. It’s just that most of us have learned how to appear as if we’re holding everything together.

Even though, by God’s grace, we no longer live in the dire conditions of the ancient world, all of us in the end are just as hungry to experience God’s mercy, compassion, and unbroken care.

And the amazing thing is that God is able and willing to deliver such care and mercy to others throughyou.