Zachary Taylor never voted in a U.S. presidential election until he was 64 years old.

That’s when the career military officer cast a ballot for himself in the 1848 election that sent him to the White House as America’s 12th chief executive.

But the record for a presidential candidate voting late in life for the first time is probably held by Nelson Mandela of South Africa.

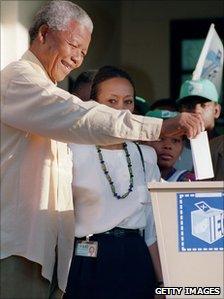

Mandela was 75 years old when, on April 27, 1994, he stepped to the ballot box and also cast a vote for himself. Millions of fellow South Africans did likewise, choosing him to become their nation’s head of state. Mandela wasn’t merely South Africa’s first democratically elected president. This was also the first time black citizens, who represented a majority of the nation’s population, had ever been empowered to vote or hold public office.

It was a moment Mandela had been working for his entire life.

Because he had protested his homeland’s racist system of apartheid, he was arrested in 1962 and charged with attempting to overthrow the country. An unmerciful judge handed down a life sentence. He spent the next 27 years behind bars, most of the time confined to a tiny cell at the notorious Robben Island prison.

In their efforts to humiliate him, Mandela’s jailers dressed him in shorts and a child’s jacket. His vision was permanently compromised because of the bright sunlight shimmering off the blocks of lime he had been forced to cut in a quarry.

Throughout his imprisonment, Mandela had symbolically represented those who were powerless. Weak. Rejected. Crushed by the Powers That Be.

When South Africa’s cultural tectonic plates finally began to shift, he was pardoned and released in 1990. The whole world applauded – and then held its breath. Most of his adult life had been stolen from him. He had suffered unjustly for almost three decades. When he became president four years later, he suddenly had the power to turn the tables on his enemies.

What would he do?

Several years ago the editors of Psychology Today asked their readers to respond to this question: “If you could push a button and thereby eliminate any person, without any repercussions to yourself, would you press that button?”

Six hundred and fifty people responded. It’s instructive to note that the average reader of Psychology Today is age 45 or younger and has at least two years of college education.

Sixty percent declared, “Yes, I would press that button!”

When asked if they had already determined specifically whom they might eliminate, men generally identified public leaders. Women tended to target ex-husbands, bosses and men who had victimized them. Some people opted for the eradication of entire groups, including violent criminals, rapists, and various ethnicities.

One 29-year-old respondent asked a question of his own: “If such a device were invented, would anyone live to tell about it?”

Mandela, suddenly and dramatically, had access to the equivalent of a Button of Revenge. He could make things right for the oppressed people he had represented for so long – including himself.

As it turns out, he did make things right – not through coercion and payback, but through the strange and unexpected strategy of forgiveness and reconciliation. He had long ago forgiven the judge and the jailers and all those who had conspired to destroy his life. As president of South Africa, he chose to lead with an outstretched hand instead of a clenched fist.

And his homeland began to heal.

Presidents Day is our annual opportunity to remember the 46 men who have served as America’s chief executive.

It’s also our opportunity, as we ponder the example of Nelson Mandela, to remember that love – just as Jesus assured us – is more transforming than hatred.

Even for presidents.