To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

Each weekday in the month of August, we will pursue “prepositional truth” by zeroing in on a single Greek preposition in a single verse, noting the theological richness so often embedded in the humble words we so often overlook.

Have you ever submitted a project or made a presentation and known, in your heart of hearts, that you had truly bombed?

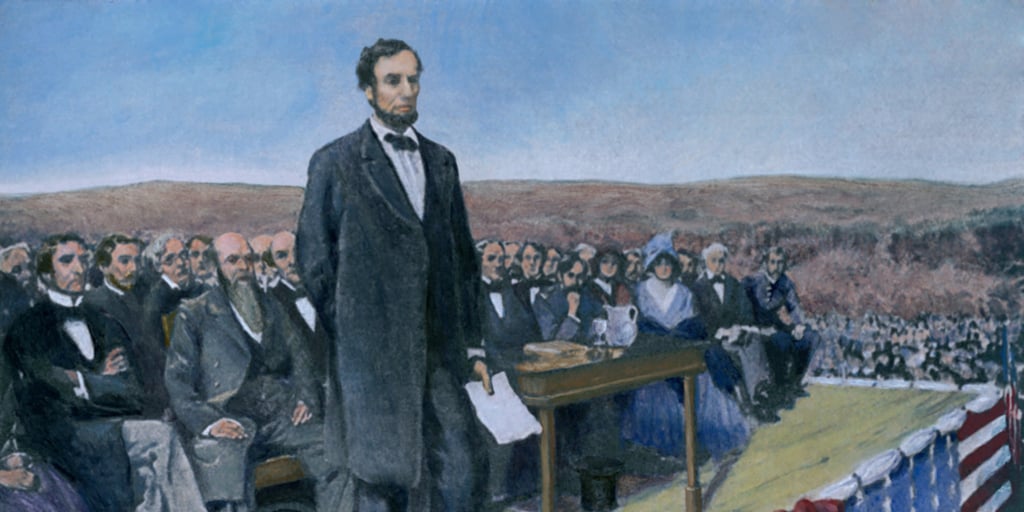

Even Abraham Lincoln was not immune from such moments of self-doubt.

Shortly after speaking to a throng in November 1863, the president turned to a friend and declared that his speech was a “flat failure.”

It didn’t help that he had spoken for only two minutes. The day’s primary orator, a pastor named Edward Everett, had spoken eloquently (and entirely from memory) for over two hours. Not that pastors have ever been known to drone on and on.

Just in case you think that negative press coverage is a modern invention, here’s what journalists had to say the next morning:

“The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat, dish-wattery utterances of the President of the United States” (The Chicago Times).

“We pass over the silly remarks of the President; for the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion be dropped over them” (The Patriot & Union of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania).

“Anything more dull and commonplace it would not be easy to reproduce” (The London Times).

And you thought you got some tough feedback in speech class. What was this dreadful speech?

Today it is known as the Gettysburg Address. It is considered one of the most inspiring and nuanced presentations ever conceived in the English language. In just ten sentences Lincoln made the case that the Civil War, which was still raging, was not merely about preserving the Union. It was really about a larger story: the struggle for human equality.

Most of us recognize the speech’s opening words: “Four score and seven years ago…” But the most compelling line is the last one, where Lincoln’s prepositions beautifully reinforce his propositions:“…that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

That trifecta – “of, by, for” – is quite possibly the most famous expression of democratic government and servant leadership ever penned.

The apostle Paul also had a brilliant way of pulling together prepositional phrases like pearls on a string. As he wraps up Romans chapter 11 – having provided an over-the-top description of how God’s eternal purposes are being worked out in human history – he closes with this doxology:

“For from (EK) him and through (DIA) him and for (EIS) him are all things. To him be the glory forever! Amen” (Romans 11:36).

Paul is straining the boundaries of language to tell us we live in a God-saturated universe. That becomes clear as we break down the prepositions.

“All things” are from (EK) God. Everything we see and experience originates in the power of the Creator Even things we are used to chalking up as human inventions – suspension bridges, iPhones, air conditioning – ultimate spring from the ingenuity God has graciously provided.

“All things” are through (DIA) God. There’s an old joke about a group of scientists who feel confident they have solved the riddle of life. They challenge God to a contest. “We can make human beings as well as you can!” God accepts the challenge and agrees to go first.

Taking a pile of dirt, God fashions a fully-formed person. “Very impressive,” admit the scientists. “Now it’s our turn.” They also take a pile of dirt – at which point God intervenes and says, “Uh, you need to go get your own dirt.”

We may congratulate ourselves on our astonishing technological advances. But the means by which such advances are accomplished – all the way from our MIT-educated minds to the most humble piles of dirt – are God’s unique and irreplaceable gifts.

“All things” are for (EIS) God. Why are there sunsets? Why do oceans team with schools of fish? Why are there rivers and mountains and glaciers and volcanic calderas? Paul declares that everything exists for God’s sake. For God’s glory. Just for the pleasure of God’s own purposes, which we may or may not ever have the privilege of discovering.

You might remember we began this month looking at the phrase “believing into,” where EIS has a directional sense – going into or towards or upon. Romans 11:38 reminds us that prepositions can have different shades of meaning in different contexts.

Abraham Lincoln didn’t live long enough to experience the total reversal in public opinion concerning his masterwork.

In fact, it wasn’t until November 2013 – 150 years after the speech at Gettysburg – that the Patriot-News of Harrisburg (successor of the Patriot & Union) printed this retraction:

“Seven score and ten years ago, the forefathers of this media institution brought forth to its audience a judgment so flawed, so tainted by hubris, so lacking in the perspective that history would bring, that it cannot remain unaddressed in our archives… the Patriot & Union failed to recognize [the speech’s] momentous importance, timeless eloquence, and lasting significance. The Patriot-News regrets the error.”

Most of us aren’t particularly comforted by the hope that 150 years from now our critics will finally come around. What can we do in the meantime?

We must trust our performances, our projects, and our reputations to God.

Prepare well. Pray. Do your very best.

Then leave the outcome in the hands of the One from whom, through whom, and for whom are all things.