To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

Seemingly out of the blue, there’s a new Indiana Jones.

Fans of the Indianapolis Colts are keeping their fingers crossed that he might represent a positive turn in their football fortunes.

NFL quarterback Daniel Jones – generally considered a first-round “draft bust” after five-and-a-half undistinguished seasons with the New York Giants – has led the Horseshoes to their first 3-0 start since 2009, a mythical time long ago when Peyton Manning was under center.

QB Jones, of course, gets his nickname from the original cinematic Indiana Jones, portrayed in five feature films by Harrison Ford, who has been thrilling audiences now for more than 40 years.

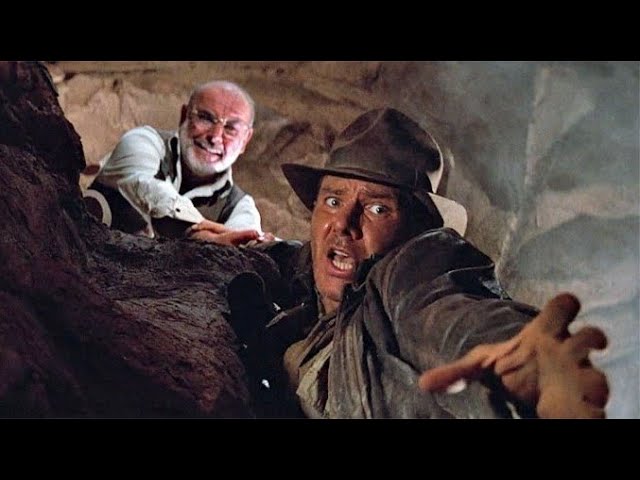

At the climax of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), the Holy Grail – the cup from which Jesus supposedly drank at the Last Supper – has fallen into an earthquake-generated crevasse. It is teetering on a ledge. Elsa, a scheming archeologist in league with the Nazis, simply must have it.

But she herself is teetering on the edge of the abyss. Indy barely holds her by her wrist, and he’s losing his grip.

She twists in an effort to reach the Grail. “Elsa, don’t do it!” he pleads. “Give me your other hand!” But she can’t take her eyes off the prize. Because she reaches for it, she plunges into the darkness.

Now it’s Indiana’s turn. After an aftershock pitches him over the edge of the crevasse, he also dangles helplessly, held only by his father’s outstretched hand.

“Give me your other hand,” pleads his dad. “I can’t hold on.” But Indy, like Elsa, is mesmerized by the Grail. He extends his fingers. “I can get it. I can almost reach it, Dad!”

What follows is one of the great ironies in the story.

Professor Henry Jones – Indy’s father, played by Sean Connery – has spent most of his adult life searching for the Holy Grail. It’s finally, almost literally, in his grasp. But he understands that even history’s most fabled artifact comes in a distant second place to hanging on to his son, from whom he has been estranged.

“Indiana,” he says, gently but firmly, “let it go.”

Indy turns away from the trinket and lets his father pull him to safety. Here’s how Steven Spielberg directed the action: Indiana Jones – Let It Go Scene

In 2010, moviegoers became acquainted with another Elsa and another “Let It Go.” The lead character of Disney’s animated feature Frozen sings a song that seems to have been memorized by every young girl in America. Elsa sings:

It’s time to see what I can do

To test the limits and break through

No right, no wrong, no rules for me

I’m free!

Let it go, let it go

I’m one with the wind and sky

Let it go, let it go

You’ll never see me cry

Here I stand

And here I’ll stay

Let the storm rage on

This is a song of self-determination. For Elsa, “freedom” means the abolition of every restraint. She will no longer conform to the expectations of others.

For all intents and purposes, “Let It Go” has become America’s cultural national anthem. No right, no wrong, no rules for me.

Henry Jones, however, is clearly pleading with his son to exercise a different kind of freedom – the freedom to say No to something that seems good in the moment in order to say Yes to that which is lastingly better. If Indiana dies to his family’s archeological aspirations, his life will be saved – and he’ll be able to enjoy the far greater treasure of his family.

When most of us come to such decisive moments, however, we find it excruciatingly difficult to let things go – even things that we know are killing us.

There’s an old story about a mother who looks out her kitchen window and sees her children playing with some baby animals. Peering a little more carefully, she’s mortified to discover that those creatures are baby skunks. “Run, children, run!” she screams. Alarmed, they each pick up a skunk and take off running.

We tend to take our skunks with us wherever we go.

We hang on to our grudges, our bitterness, our resolutions to get even, our sense of failure, our overwhelming unworthiness in the presence of a holy God. We can hardly imagine life without such thoughts.

But our heavenly Father says, gently but firmly, “It’s time to let them go.”

Author John Ortberg, in his recent book Steps, notes that on the same night Jesus sat at the Last Supper with his friends, he wrestled with his awareness of the agony that lay before him. “Father, if it’s possible, may this cup pass from me.”

In ancient Judaism, “drinking the cup” meant surrendering to God’s will, accepting God’s justice. Jesus wondered if perhaps there was another way.

And his Father said, “My Son, let it go.”

Because he did so, Jesus received new life three days later – the same deep, lasting Life that can now be ours by faith.

Even at this very moment, you are being held by your Father’s strong grip.

Will you turn away from lesser things and let him lift you into the life you’ve always wanted?