Throughout Lent, we’re exploring the parables of Jesus – the two dozen or so stories that were his chief means of describing the reality of God’s rule on earth.

A long, long time ago, when I was in the fifth grade, male and female students went to separate classes twice each week.

The girls walked down the hall to the Home Economics room, where they learned skills related to sewing and cooking. The boys, meanwhile, strode in the opposite direction to the “Shop” room, where we were schooled in Industrial Arts.

Shop class was fun. It was a delightful diversion from math and English. Over the course of a year we would undertake simple carpentry projects, build electric circuits, and solder rivets. Since I have rarely engaged in such activities over the past half century, I often think how wonderful and useful it would have been to learn how to cook and sew.

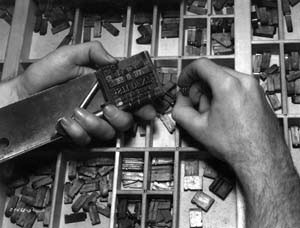

In Shop class we were taught how to hand-set type, painstakingly creating printing blocks one letter at a time. It was the mid-1960s, and no one could see that the digital revolution would soon bring personal computers and laser printers within everyone’s reach. Learning how to hand-set type was like learning how to hand-dip candles just before the invention of the light bulb. Block printing is a charming skill from a bye-gone era.

I especially remember the challenge of using spacers – little pieces of lead of varying sizes – that were inserted between words to create margins. In the world of printing, “justification” is the practice of ensuring that the margins are straight. The edge of each line of text must be brought into proper alignment with everything else on the page.

One of the glorious capabilities of word processors is that, with a single keystroke, margins can be justified to the left or the right. The text can even be centered in the middle. Those enrolled in Shop class at Indianapolis Public School 66 could only have dreamed of such miracles.

In Luke chapter 10, Jesus is confronted by a lawyer – an expert in Jewish moral legislation – who hopes to do something that no human being can ever do:

He wants to justify himself.

Generations of rabbis had debated which Old Testament law deserved to be called Most Important. What does this new Galilean teacher think? Jesus answers, “Love God and love people. If you abandon yourself to God and show up for your neighbor, everything else will fall into place.”

That’s wonderfully straightforward. But the lawyer has a card up his sleeve. “He wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, ‘And who is my neighbor?’” (v.29)

The lawyer is looking for loopholes. He wants to straighten his own margins, to bring himself into proper alignment with God so he can be deserving of eternal life. He’s looking for the little spacers, the little activities he can undertake to make everything in his world sit right.

But we cannot justify ourselves. Only God is able to put someone in proper alignment with God.

The lawyer resorts to a bit of exegesis. “And who exactly is my neighbor? How many people are you saying I have to be nice to?” Commenting on this question, author Frederick Buechner writes:

He wanted a legal definition he could refer to in case the question of loving (a neighbor) ever happened to come up. He presumably wanted something on the order of: “A neighbor (hereinafter referred to as the party of the first part) is to be construed as meaning a person of Jewish descent whose legal residence is within a radius of no more than three statute miles from one’s own legal residence unless there is another person of Jewish descent (hereinafter to be referred to as the party of the second part) living closer to the party of the first part than one is oneself, in which case the party of the second part is to be construed as neighbor to the party of the first part and one is oneself relieved of all responsibility of any sort or kind whatsoever.” (from “Wishful Thinking: A Seeker’s ABC”)

Jesus, however, is not into legal exegesis. Instead, he tells an imaginative parable that is as startling in its implications today as it was to its original audience 20 centuries ago.

Let’s try to step into the lawyer’s sandals. Why is he hesitant to be a neighbor to people in need?

He’s presumably up against the barriers of race, place, grace, and face. So are we.

Race is the reflex to distance ourselves from other ethnicities. Racial tensions were severe in the Middle East in Jesus’ time, and remain so today. It’s safe to say that America has never been free from the underlying suspicion that people of different backgrounds might not deserve the same kind of love and compassion as “our own people.”

Place is the assumption that proximity matters. If I don’t live in an urban neighborhood, why should I care about the hurting people on those streets? Even if the blessings of modern technology allow me to fly to any spot on the face of the earth within 24 hours, why should I fret about the populations of other continents?

Grace is the conviction that if my life is going well and someone else is just getting by, it’s probably because I deserve God’s blessings and that person is under God’s judgment. This line of thought quickly degenerates into pride and cruelty. God forgive us for thinking that our blessings are only about us.

Face is the fallacy that I don’t need to help others if I can’t see them. If I don’t know someone’s name or story, perhaps I won’t be held accountable. May God open our eyes.

The lawyer is looking for the last little spacer that will allow him to go to bed at night knowing the margins of his life are aligned with God’s highest values.

But Jesus redirects the conversation by telling what has come to be known as the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

Tomorrow we’ll dive into the details of this extraordinary story.