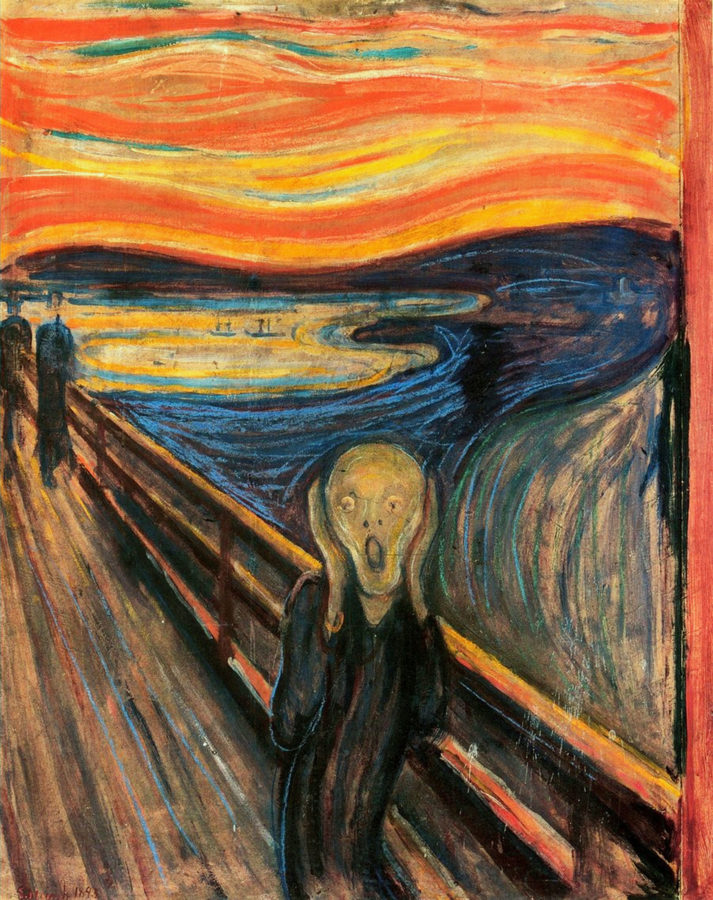

Journalist Arthur Lubow called it “an icon of modern art, a Mona Lisa for our time.”

If The Scream is representative of the spirit of our age, then we live in a deeply unsettling period of history.

The Norwegian artist Edvard Munch never concealed his insecurities. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was five. His favorite sister Sophie died of the same disease less than a decade later. Terrified that he would not be able to survive his own childhood, fearful that he would be overtaken by the mental illness that seemed to stalk his family, he transformed his anxieties into some of the most memorable artistic creations of the early 20th century.

A number of Munch’s paintings pack the emotional punch of bad dreams. He made use of vivid colors, distorted images, and sinister figures to convey a sense of dread.

The Scream was inspired by a walk at sunset in the city of Kristiania sometime around 1893. He later wrote, “I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fiord. The sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red… I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature… It seemed to me that I heard the scream… The color shrieked.”

At least one historian has speculated that the blood-red skies represented the remnants of the powerful explosion of the Indonesian volcano Krakatoa, which erupted in 1883 and impacted our planet’s meteorology for the next decade.

Others have noted that from the vantage point of Munch’s painting he could see both a slaughterhouse and the asylum where one of his younger sisters was being treated for psychosis – features that may have heightened his angst.

The image got under his skin to such a degree that he created four versions of The Scream between 1893 and 1910 – two in oils and two in pastels. One of the pastels was recently auctioned for the fourth highest price ever paid for a work of art.

The shriek of the agonized figure seems to have anticipated the horrors of the coming century, with its trench warfare, blitzkriegs, genocides, and nuclear weapons.

Some years ago, art experts examining the version that hangs in the National Museum of Norway discovered a message scrawled in pencil in small letters in the upper left hand corner. It said, “Could only have been painted by a madman.” At first they assumed it was the work of a critic or a vandal. But analysis has proved that Munch himself – terrified of going insane – defaced his own painting.

The image has become an indelible part of American pop culture. Think of Kevin screaming in the bathroom in Home Alone (with his hands on the sides of his head), and the slasher movie Scream and its three sequels, each of which features a killer who wears a Munch-inspired white mask. Scream 5, which no one seems to have asked for, is currently in post-production.

The Scream presents itself as Reality. This is what life is like for modern people living in an angst-ridden world.

The Bible, by comparison, appears to be a collection of happy thoughts for people who probably need to get out more often.

Think about it. Many of those “you-can-be-rich-and-successful” seminars trot out positive-thinking scripture verses to motivate their participants. Uplifting Bible texts routinely appear in the inspiring books we present to high school and college graduates every spring. People who have never actually read the Bible may be forgiven for thinking it’s about as edgy as a Hallmark greeting card.

Don’t you believe it.

The 150 psalms of the Old Testament are the record of the emotional life of God’s Chosen People. At least half of them are “laments” – cries of the heart in the face of physical suffering, betrayal, bereavement, and deep personal loss. Some of the psalmists shake their fists at God. They get angry. They weep. They scream.

The darkest of the dark is Psalm 88, whose author was clearly in a very bad place:

“I am overwhelmed with troubles, and my life draws near to death.” (verse 3) “You have put me in the lowest pit, in the darkest depths.” (verse 6) “I am confined and cannot escape; my eyes are dim with grief.” (vs. 8-9) “Why, Lord, do you reject me and hide your face from me?” (verse 14) “Your wrath has swept over me; your terrors have destroyed me.” (verse 16)

The psalmist saves the worst for last. “You have taken from me friend and neighbor – darkness is my closest friend.” (verse 18)

That has to qualify as the most depressing finale to any chapter in the Bible.

But it’s real. It’s raw. It’s honest. And many of us have felt exactly the same way. God doesn’t pretend that his own people will somehow be immune from shrieking.

So where’s the hope in Psalm 88?

It’s found in only one place – in the very first verse: “Lord, you are the God who saves me…” Whenever we pray, whenever we cry out, we are presenting ourselves to the only One who can rescue us. Perhaps all we can offer after that are sobs, tears, and complaints. But God can handle it.

In fact, he moves toward us, not farther away. “The Lord is close to the brokenhearted and saves those who are crushed in spirit.” (Psalm 34:18)

Life can make us scream.

But God can turn our most anguished moments into our most important opportunities to cling to him.