If you scan the horizon of professional sports in America, it’s impossible to miss the African American superstars.

Who’s the greatest basketball player of all time? The current contenders are Michael Jordan and LeBron James, but MJ himself believes no one will ever surpass the accomplishments of Bill Russell.

Cheryl Miller, Candace Parker, Tamika Catchings, and Maya Moore might be chiseled one day onto the Mt. Rushmore of women’s basketball. All are black.

You can’t talk about lifetime excellence in golf without mentioning Tiger Woods. And tennis star Serena Williams is arguably the greatest female athlete of all time.

In celebration of the NFL’s recently completed 100th season, various sportswriters have endeavored to identify the 100 greatest players ever to take the field. The order of the names varies from poll to poll, but Jerry Rice, Jim Brown, Lawrence Taylor, Reggie White, and Walter Payton are almost always at or near the top.

And what about baseball? You can’t tell the story of the past 60 years without mentioning Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Roberto Clemente, and countless other players of color.

None of these careers would have been possible unless someone broke the color barrier in professional sports. Someone had to challenge the unwritten but unbending “gentleman’s agreement” embraced by team owners that blacks must never be allowed to compete with whites on the diamond, the gridiron, or the court. It would take a special someone to endure the open hostility and abuse that would come his way for daring to buck the system.

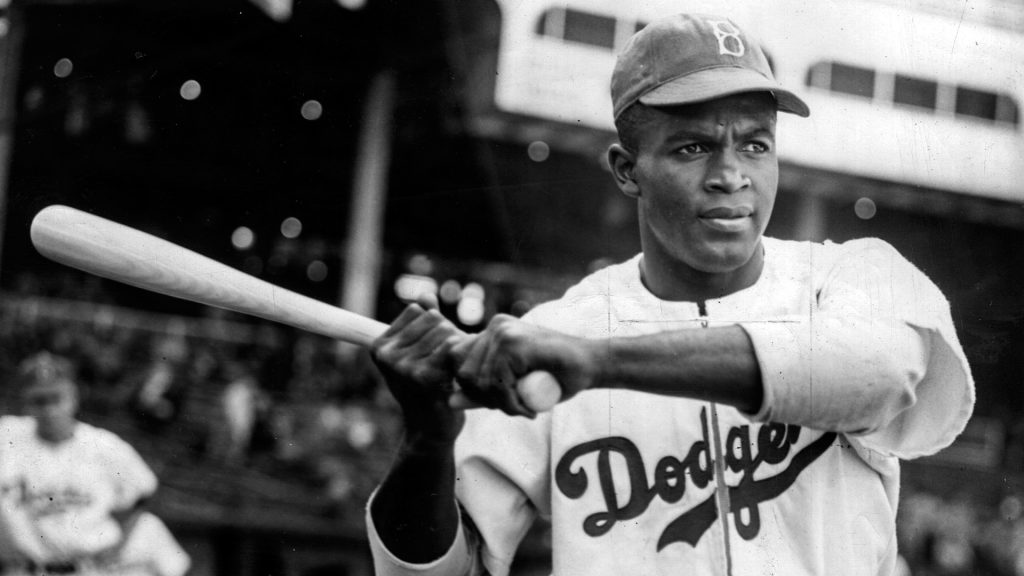

That someone turned out to be Jackie Robinson, a 28-year-old African American who stepped onto the baseball field as a Brooklyn Dodger on April 15, 1947.

The quest for racial integration in American life was accelerated by World War II. Young black soldiers, just like young white soldiers, had put their lives on the line. If blacks went to war to die for democracy, why shouldn’t they be allowed to play baseball? More and more Americans realized that the country that had just won the war was now in danger of losing the peace.

Dodgers owner Branch Rickey made up his mind to end the hypocrisy.

For several years he secretly scouted the best players in the Negro Leagues, searching for someone who was both skilled enough to bear the burden of representing every African American athlete (a daunting enough task), yet courageous enough to withstand the inevitable social blowback.

Robinson was an extraordinary baseball player. He also had a temper. Rickey knew that once Jackie took the field, the Great Experiment would require him to check his emotions.

The owner asked him directly, “Have you got the guts to play the game no matter what happens?” Could he hold his head high and not strike back against his detractors? Robinson said yes.

It wasn’t easy.

As graphically depicted in the movie 42 (the number Robinson wore throughout his career), opposing fans called him every name in the book. Some of his own teammates circulated a petition to send him packing. As a black man entering what had always been a white man’s space, he experienced firsthand the Jim Crow culture that insisted on separate hotels, separate restaurants, and even separate laundry piles for Negro players. Because spring training typically took place in the segregated South, Branch Rickey built “Dodgertown” on private land in Florida, creating an integrated community where Robinson could live and play as an equal.

The hardest part was exercising restraint.

Check out this moment from the film in which Enos Slaughter, a slugger for the St. Louis Cardinals, goes out of his way to spike Robinson (portrayed by the late Chadwick Boseman) as the Dodger covers first base: 42 Movie CLIP – Get Me Up (2013) – Jackie Robinson Movie HD – YouTube. While Dodger players plot to get revenge by beaning the next batter, Harrison Ford, playing Branch Rickey, whispers under his breath that Robinson needs to get up. He can’t let his opponents destroy his will to keep going.

The greatness of Jackie Robinson is that he chose to endure the indignities of being the chief pioneer of racial integration in American sports.

And how did things go in the realm of hits and runs?

Robinson, on his way to the Baseball Hall of Fame, was chosen 1947 Rookie of the Year and led the Dodgers to the World Series. Brooklyn would win five more pennants and a world championship before he retired in 1956. Every step of the way his game was characterized by courage and grace.

It’s worth noting that Branch Rickey knew that Jackie had to become a leader. After his third year in the league, he turned his star loose. Robinson was empowered to stand up to the abuse, argue bad calls, and literally push back in the heat of the moment. He went on to become a national civil rights leader, advocating for integrated school and working for the elimination of Jim Crow legislation in the South. He said in 1963, “No Negro has it made regardless of his fame, position, or money, until the most underprivileged Negro enjoys his rights as a free man.”

Rickey, meanwhile, was an unusual sports executive.

He believed in God and worried that things would not go well for any of us at the Judgment if we were part of a culture that held people back.

He often repeated his family motto which he had learned as a child: “Make first things first, seek the kingdom of God, and make yourself an example.”

Jackie Robinson may have already broken the color barrier in professional sports.

Now we have the opportunity to discern how we can be an example in a world that cries out every day for transformation.