To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

On a cold winter night in Chicago in 1927, Buckminster Fuller calculated how long it would take for him to die of hypothermia in the frigid waters of Lake Michigan.

He stood, despondent, on a deserted stretch of shoreline north of the city. At age 32 he had no job prospects, no savings, and no way to provide for the little girl his wife had recently brought into the world.

So he would kill himself by swimming out into the lake until he could swim no more.

Before he took the plunge, however, he sensed that he was surrounded by light. An inner voice seemed to rebuke him: “You do not have the right to eliminate yourself. You do not belong to you. You belong to the universe.” Suddenly he was overcome by the conviction that his life had a solemn purpose. He was called to share his first-rate mind with the rest of the world.

Fuller returned home and explained to his wife that he didn’t need a job. All their needs would be met. He simply needed to think. He resolved not to utter a word until his thoughts had taken final form. Fuller’s season of silence lasted two years, during which time he filled 5,000 pages with notes. As Jonathon Keats writes in his biography of Fuller, You Belong to the Universe, “His jottings and sketches revealed the secret to making the whole human race successful for all eternity.”

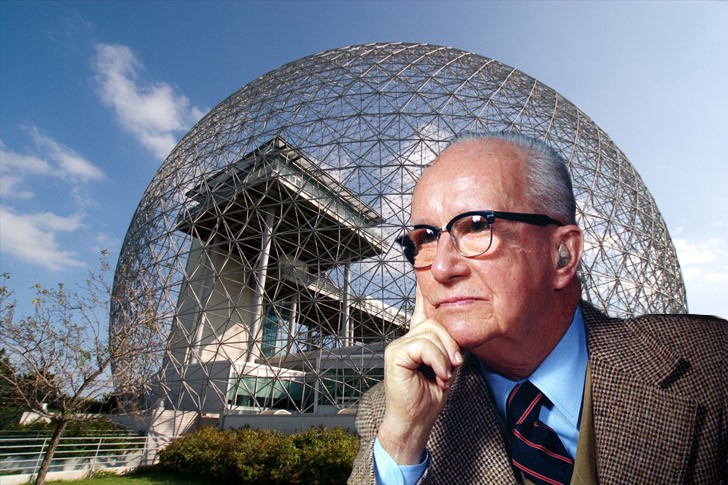

Fuller went on to become a world-renowned architect, futurist, systems theorist, and philosopher – a “comprehensive anticipatory design scientist,” as he liked to call himself.

That’s an amazing story. Rags to riches. Despair to triumph. Buckminster Fuller loved to tell it, over and over again, throughout his long life.

But as Keats points out, he also loved to change the details. Fuller’s life story was a personally crafted myth designed to prove that he was the one person brilliant enough to solve the world’s problems. Historians have never found evidence that he contemplated suicide that wintry night on the shores of Lake Michigan. Nor was he unemployed for more than a few weeks. He sold asbestos flooring after 1927, a job which no doubt required that he speak on a regular basis to his clients and supervisors.

Nevertheless, Fuller’s audacious claims and out-of-the-box ideas helped him become a kind of global cult figure.

His central purpose was to ensure that humanity would achieve “eternal” success. He continually asked, “What’s wrong with the world, and what are we going to do about it?” Then he would propose solutions – ideas which he believed were in fact the one-and-only solutions to our planet’s crises.

Humanity needed better housing. So he invented the Dymaxion house, a mushroom-shaped single-family dwelling that could be picked up and moved from place to place. “Dymaxion,” incidentally, was a term cobbled together from three of Fuller’s favorite words: dynamic, maximum, and tension. Humanity needed cheaper, more reliable transportation. So he crafted the Dymaxion car, a futuristic, jelly-bean shaped automobile that looked like something right out of The Jetsons.

Humanity needed better architecture and safer, cleaner cities. So he popularized the geodesic dome. Think of Spaceship Earth (another term coined by Fuller), the spectacular dome that greets visitors to Epcot Center in Florida’s Disney World. Fuller proposed covering large parts of Manhattan with geodesic domes in order to regulate pollution, crime, and other urban struggles.

The world’s problems could be solved, he insisted, if only people embraced his beliefs. Fuller, certain that he was right about everything, dismissed alternative perspectives as the detritus of lesser minds.

Almost 40 years after his death, Buckminster Fuller is remembered as a hopeful, optimistic, egocentric dreamer.

People have never stopped asking his primary question: What’s wrong with the world, and what are we going to do about it?

That question, in fact, was proposed by The London Times around the time of the First World War. The editor sent out an inquiry to a number of famous authors: “What’s wrong with the world today?” The most memorable response came from a Christian novelist and social critic. It was just seven words long: “Dear Sir, I am. Yours, G.K. Chesterton.”

The world’s most intractable problems aren’t “out there” somewhere.

They fester within stubborn, rebellious, fearful human hearts. And no amount of creative engineering is ever going to set things right.

But God has done something about the world’s greatest problems.

“This is how much God loved the world: He gave his Son, his one and only Son. And this is why: so that no one need be destroyed; by believing in him, anyone can have a whole and lasting life. God didn’t go to all the trouble of sending his Son merely to point an accusing finger, telling the world how bad it was. He came to help, to put the world right again” (John 3:16-17).

Innovation, social justice, and public service will always be good gifts to the world. But lasting change must inevitably include the transformation of human hearts.

And we don’t need a Dymaxion Bible to know that can happen only by the grace of God.