To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

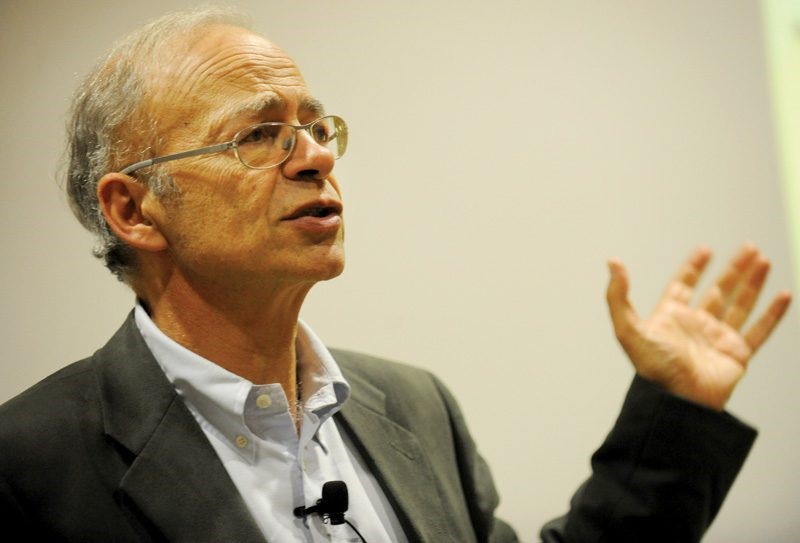

Some people are inspired by Peter Singer.

Others think he is the most dangerous intellectual in America.

Everyone at least agrees on this: The Australian-born Princeton University emeritus professor is never boring.

Singer is a bioethicist. He specializes in how scientific principles should lead human beings to think and behave.

He wrote the main article concerning ethics for the Encyclopedia Britannica. If you were born after 1990, that is a large set of books that used to be displayed on your grandparents’ living room shelves, which were excellent for pressing prom flowers.

Singer is an atheist who describes himself as a hedonistic utilitarian. That means he believes that seeking “the greatest pleasure for the greatest number of people” is the surest guide to making wise decisions.

Singer would include a great many animals in that ethical formulation. As one of the world’s most eloquent defenders of animal rights, he has given up eating mussels and oysters. “They probably don’t suffer,” he says, “but you never know.”

Singer’s detractors aren’t particularly up in arms about the rights of oysters. But they are powerfully provoked by his perspectives on human rights.

Is all of human life sacred and worthy of respect? Singer says no. He believes the concept of the sanctity of human life is outdated and unscientific.

He asserts that personhood, and thus the right to exist, is tied to a being’s capacity to have preferences and make choices. That means that defective infants and some older adults don’t really qualify as persons.

Singer suggests that if parents don’t want to raise a developmentally disabled child, they should have the right to end its existence. “Killing a newborn baby is never equivalent to killing a person, a being who wants to go on living.” Just because an embryo is a living human being (something he clearly affirms), doesn’t mean it’s a person worthy of protection and honor.

Likewise, older people who have lost the capacity to make meaningful choices may be euthanized.

He is sympathetic to the vision of bioengineering “headless clones” – carbon copies of ourselves (minus brains), kept alive by machines, that might be available as living repositories of spare parts.

As a utilitarian, Singer is committed to ethical choices that work in the real world. It’s worth noting, therefore, what happened when his own mother showed signs of dementia.

Despite the fact that he had previously affirmed his openness to ending his mother’s life when she became infirm, he continued to provide her with financial support.

“I think this has made me see how the issues of someone with these kinds of problems are really very difficult,” he admitted. “Perhaps it is more difficult than I thought before, because it’s different when it’s your mother.”

This is when we must ask Peter Singer, with gentleness: If there is no ultimate value to human life, why should anything be different when it’s your mother?

The irony is that Singer’s Jewish parents, who grew up in Austria, barely escaped Hitler’s purges in 1938 by emigrating to Australia. Grandparents on both sides of his family died in Nazi extermination camps. The Third Reich systematically eliminated not only Jews, gypsies, pastors, homosexuals, and political rivals, but those who were mentally and physically challenged – individuals whom Hitler declared to be “unworthy of life.”

If God is God, and human beings are made in God’s image, then all human beings are worthy of life – especially those among us who are the most vulnerable.

The ultimate scriptural vindication of that high view of human existence emerges in David’s words in Psalm 139:13-16:

For you [O Lord] created my inmost being;

you knit me together in my mother’s womb.

I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made;

your works are wonderful,

I know that full well.

My frame was not hidden from you

when I was made in the secret place,

when I was woven together in the depths of the earth.

Your eyes saw my unformed body;

all the days ordained for me were written in your book

before one of them came to be.

The lives of the unborn, newborns, physically and mentally challenged, and old and infirm all matter eternally.

Not because we have found them to be “useful,” helpful, or worth keeping around.

But just because they are eternally loved.