To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

In 1903, a photographer from Seattle named Edward S. Curtis had a big idea.

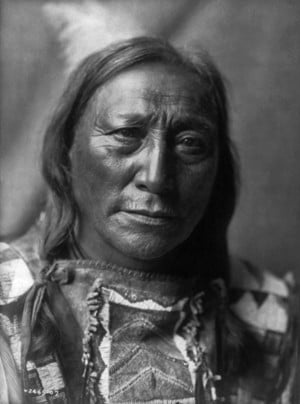

He dreamed of capturing the faces and the lives of North American Indians, something no one else had ever attempted.

Curtis knew that the clock was ticking. The “old ways” of the First Peoples (and the people themselves) were rapidly disappearing.

When Columbus stepped ashore at the outskirts of the New World in 1492, it’s estimated that the North American continent was home to about 60 million Indians. By Curtis’ time, less than 250,000 remained. The rest had succumbed to slaughter, exile, and imported diseases for which they had no immunity.

Curtis’ big idea was to invest decades in visiting at least 80 remaining tribal groups from Arizona to Alaska, win their trust, and progressively capture images that would allow future generations to appreciate Native American culture.

But when he visited Washington D.C. in search of support, people laughed.

The curators of the Smithsonian were put off by the fact that Curtis had no education. He was a grade school dropout, for crying out loud. He had no technical training. Who did he think he was?

More significantly, there was very little affection for Indians.

Teddy Roosevelt, who was president at the time and one of America’s most progressive leaders, had famously declared that he was almost certain that 9 out of 10 Indians were better off dead, “and I wouldn’t want to inquire too carefully into the 10th.”

Native Americans were popularly depicted as dirty, lazy, immoral, sub-human pagans – a caricature that was reinforced by the “Indian experts” in academia, many of whom, incredibly, had never actually stood face to face with a live Native American.

Curtis knew, however, that Roosevelt had a special circle of friends who were pursuing a big idea of their own: the conservation of America’s irreplaceable natural resources.

How could he convince TR that Native Americans were one of those irreplaceable treasures?

When Curtis had the chance to visit the White House, he asked the president if he could photograph his children. Yes, of course, Roosevelt answered.

The pictures were breathtaking. Curtis had a knack of accomplishing something that was beyond most photographers: He could find the humanity in his subjects. TR himself posed for Curtis. He was so pleased with the result that he later made sure that picture accompanied his autobiography.

Roosevelt’s attitude began to thaw. Could he have a look at the photographs of Indians that Curtis had already taken, the ones he had brought along with him?

It gradually dawned on the president that this photographer’s Big Idea was an idea he needed to support, heart and soul.

With Roosevelt’s endorsement, Edward Curtis spent virtually the remainder of his adult life pursuing his photographic mission.

Over a period of 33 years, he carefully crafted 20 spectacular volumes. They included over 2,000 images of vanishing peoples representing a vanishing way of life. Only 220 complete sets (a single set takes up five feet of bookshelf space) were originally produced. After almost a century, they are finally being republished.

Here’s one of a number of sites where you can glimpse examples of Curtis’ work.

Along the way, the photographer became committed to preserving Indian culture. Almost singlehandedly, he wrote down 75 tribal languages which would otherwise have been lost. He wrote out hundreds of Native American songs.

When the Hopi tribe of the desert Southwest recently launched an initiative to introduce their children to their most ancient traditions, Curtis’ volume proved to be the most valuable resource.

What’s so special about his pictures?

Curtis believed that Native Americans were just like everyone else. His photographs show people who felt love, hope, and fear. They adored their children, laughed at jokes, and clung to a fierce sense of pride. His photographs, in other words, turned people who were rejected and misunderstood into full-fledged human beings.

Is there someone in your life whom you’d just as soon see vanish from the face of the earth?

Understanding always begins with reverence for another person’s humanity.

The people who work for that company that is cutting into your profits or jeopardizing your retirement nest egg aren’t “total losers.” They are men and women who are trying, just like you, to make their way through life.

There might be days in which it feels as if your ex is a monster who should be locked away in a windowless dungeon. But he or she is a person created in the image of God, and for whom Jesus was gladly willing to die on the cross.

It may seem impossible to ever be at peace with someone whose vote always cancels out your vote – that sadly deluded person who watches the wrong news programs and embraces perspectives straight from the Abyss.

But how you respond to the challenge of relating to that person may actually represent the current cutting edge of your spiritual life. It could be the very place where God is most at work in your heart.

The first step to restoring hope to our relationships is to reclaim our awareness that we share every other person’s humanity.

Believing that, and acting on it for Jesus’ sake, is a key to helping bring about a world worth living in.

If only we can picture it.