Father Gregory Boyle is the founder and director of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles, a widely acclaimed gang intervention program.

It’s a ministry that involves considerable heartache.

As of 2017 and the release of his book Barking to the Choir: The Power of Radical Kinship, Boyle had presided at the funerals of 220 gang members, most of whom had died violently.

Yet many of those young men had also experienced a measure of hope and redemption in this world.

When asked to speak a few years ago to a group of 600 social workers in Richmond, Virginia, Father Greg brought along a pair of “trainees” – former gang members who are learning to tell their stories to the world.

One of them was Sergio – tattooed, in his 20’s, a heroin addict and glue sniffer who had been homeless for several stretches and had spent time in prison for crimes that began when he was still in elementary school. He had begun his time at Homeboy in the Humble Place – that is, as part of the janitorial team – before becoming a trusted member of the Substance Abuse Recovery Team, where he was helping younger kids give sobriety a try.

Sergio had never stood before a crowded room of nicely-dressed people.

“I guess you could say my mom and me, well, we didn’t get along so good,” he said haltingly. “I think I was six when she looked at me and said, ‘Why don’t you just kill yourself? You’re such a burden to me.’”

All 600 social workers gasped. He was barely two sentences into his story, and no one could breathe.

“I think I was like nine years old when she drove me to the deepest part of Baja California, walked me up to this orphanage and said, ‘I found this kid.’” Sergio was abandoned there by his mother. It took 90 days for his grandmother to convince her daughter to tell her the location so she could go there and rescue him.

Boyle reports that Sergio then paused, searching for what to say next. “My mom beat me every day of my elementary school years with things you could imagine, and things you couldn’t.”

Every day he wore three T-shirts to school. The innermost shirt caught the seeping blood. The second shirt soaked up what was left. “The third T-shirt, you couldn’t see no blood,” said Sergio. “Kids at school would make fun of me. ‘Hey fool, it’s 100 degrees. Why you wearing three T-shirts?’”

Sergio paused again, then continued, “I wore three T-shirts well into my adult years, because I was ashamed of my wounds. I didn’t want no one to see ‘em. But now I welcome my wounds. I run my fingers over my scars. My wounds are my friends. After all, how can I help others to heal if I don’t welcome my wounds?”

Father Greg writes, “And awe came upon everyone.”

When we look closely at the lyrics of the world’s most famous Christmas carols, it’s surprising how often they address not just the birth of Jesus but also his suffering and death. It’s as if the first chapter of his story can’t be told without mentioning the last. Sometimes the carols themselves arose from experiences of suffering.

In 1865 an Englishman named William Chatterton Dix, who helped manage an insurance company, was struck by a severe illness.

His recovery prompted a personal spiritual revival, during which he wrote a handful of hymns. One of them was called “A Manger Throne.” Years later it was set to the tune of “Greensleeves,” a popular English folk song.

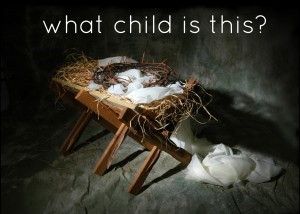

Today we know it as What Child is This?, a gentle carol that wrestles with fierce questions:

How can a baby be God? And if that baby really is God, why is he stuck in such humbling circumstances? And why in the world would God, the Creator of the cosmos, openly embrace personal suffering?

None of that was in line with people’s messianic expectations during Bible times. Here are Dix’s words:

What Child is this who, laid to rest on Mary’s lap is sleeping? Whom angels greet with anthems sweet, while shepherds watch are keeping?

This, this is Christ the King, whom shepherds guard and angels sing. Haste, haste, to bring Him laud, the Babe, the Son of Mary.

Why lies He in such mean estate, where ox and ass are feeding? Good Christians, fear, for sinners here the silent Word is pleading.

Nails, spear shall pierce Him through, the cross be borne for me, for you. Hail, hail the Word made flesh, the Babe, the Son of Mary.

So bring Him incense, gold, and myrrh, come peasant, king to own Him. The King of kings salvation brings, let loving hearts enthrone Him.

Raise, raise a song on high, the virgin sings her lullaby. Joy, joy for Christ is born, the Babe, the Son of Mary.

Here’s a contemporary version of this carol by Michael W. Smith and Martina McBride.

It’s beautiful. But like most modern recordings, it omits the original second verse with its mention of nails, spear, and cross.

Jesus, however, would no doubt resonate with Sergio.

They both were wounded, yes. But they welcomed their wounds.

For how can we help others to heal unless we welcome our wounds?