Throughout Lent, we’re exploring the parables of Jesus – the two dozen or so stories that were his chief means of describing the reality of God’s rule on earth.

For a creature that never actually existed, unicorns are very much in fashion.

Depending on which dictionary you’re consulting, a unicorn is either a Silicon Valley start-up company worth at least a billion dollars; a white, horse-like creature with a single horn growing from its forehead; or what thousands of young girls are hoping to look like the next time they go trick-or-treating.

During the Middle Ages, beastiaries – illustrated books that contained descriptions of animals, plants, and other natural phenomena – declared that unicorns, though shy and rare, were quite real. Julius Caesar insisted he had seen a few during his military campaigns in Gaul (present-day France). Most peasants knew at least one friend, or a friend of a friend, who claimed to have encountered one late at night in the middle of the forest. Unicorns, in other words, were the medieval equivalent of Bigfoot.

They were assumed to be swift, fiercely wild, and impossible to capture. Their magical horns were said to be capable of healing numerous afflictions.

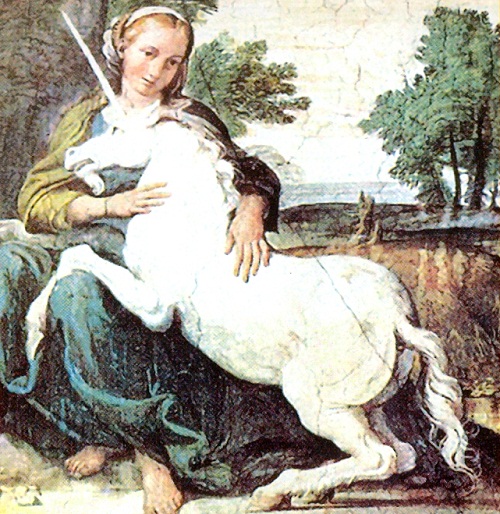

There was, however, one assured way to catch a unicorn. The secret was to invite a young virgin to sit down in a quiet clearing. After a while a unicorn would approach her and lay its head in her lap, rendering itself vulnerable to hunters.

In the medieval mind, the unicorn became a symbol of Christ. After all, isn’t this what Jesus did? The second person of the Trinity, who had existed from before the creation of the world, offered himself as a helpless infant to the lap of the Virgin Mary. And at the end of his life on earth, he willingly surrendered himself to the “hunters” who nailed him to the cross.

There are only three parables that appear in all three synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke): the Parable of the Four Soils, the Parable of the Mustard Seed, and this sharp-edged story that expresses something of the “unicorn life” of Jesus:

“Here’s another story. Listen closely. There was once a man, a wealthy farmer, who planted a vineyard. He fenced it, dug a winepress, put up a watchtower, then turned it over to the farmhands and went off on a trip. When it was time to harvest the grapes, he sent his servants back to collect his profits. The farmhands grabbed the first servant and beat him up. The next one they murdered. They threw stones at the third but he got away. The owner tried again, sending more servants. They got the same treatment. The owner was at the end of his rope. He decided to send his son. ‘Surely,’ he thought, ‘they will respect my son.’

“But when the farmhands saw the son arrive, they rubbed their hands in greed. ‘This is the heir! Let’s kill him and have it all for ourselves.’ They grabbed him, threw him out, and killed him. Now, when the owner of the vineyard arrives home from his trip, what do you think he will do to the farmhands?”

“He’ll kill them—a rotten bunch, and good riddance,” they answered. “Then he’ll assign the vineyard to farmhands who will hand over the profits when it’s time.” Jesus said, “Right—and you can read it for yourselves in your Bibles:

The stone the masons threw out

is now the cornerstone.

This is God’s work;

we rub our eyes, we can hardly believe it!

“This is the way it is with you. God’s kingdom will be taken back from you and handed over to a people who will live out a kingdom life. Whoever stumbles on this Stone gets shattered; whoever the Stone falls on gets smashed.” (Matthew 21:33-44, “The Message”)

Here we see an economic arrangement that was fairly common in the time of Jesus. A rich man creates a vineyard and then becomes an off-site landlord. He hires workers who are responsible for the harvest. At the end of the growing season, he sends servants to collect what rightly belongs to him.

For the original listeners, the historical connections in this story were a no-brainer. In the Old Testament, the nation of Israel is called God’s vineyard. The workers are the religious leaders who are responsible for its fruit. God, the rich landowner, repeatedly sends his servants (the prophets of old) to the vineyard at harvest time. But one after another, the hired hands seize them, beat them, and even kill them.

Then God does something outrageous. He risks the life of his son. “Surely they will respect my son,” he says.

But the workers have become so audacious that they think killing the master’s son will be their ticket to the good life. In a part of the world where possession is nine-tenths of the law, they conclude that if the master never comes back to check on his vineyard, and if they get rid of his one and only heir, all of this will become theirs.

They have gambled big. Now they are going to lose big. Jesus asks his audience, “When the owner of the vineyard comes, what will he do to those farmhands?”

As Bible scholar Dale Bruner points out, this is a great teaching technique: Put yourself in the place of God. What would you do? “Those wretches will be brought to a wretched end!” they answer. “That’s right,” says Jesus. And now he has them. They have pronounced their own sentence. But he also has us – because this story isn’t just a recitation of the history of Israel. This is also our story – the story of God being patient and kind with us, even when we insist on going our own way.

Here we need to pause and acknowledge something that Christians have long failed to get right: The Jewish nation was not singularly responsible for the death of Jesus.

The historian Thomas Cahill suggests that the way Christians have ridiculed, persecuted, and even massacred Jews over the centuries – labeling them Christ-killers – is “the lasting shame of Christianity, even more of a blot than its centuries of crusades against Muslim ‘infidels.’” Cahill asserts that so-called followers of Jesus have caused far more harm to Jesus himself than Jews ever caused, for the simple reason that the Christians’ brutal treatment of the Jews has so obviously violated Jesus’ teachings.

Let us remember Jesus’ amazing statement as he prepared for the cross: “No one takes [my life] from me, but I lay it down of my own accord.” (John 10:18) Jesus is the unicorn choosing to walk into the clearing.

What is the best name for this story of the workers in the vineyard? Dale Bruner suggests the Parable of the Many Sendings or Many Chances.

How have we responded to the many ways in which God is trying to grab our attention? The make-or-break moment in the story is how the workers respond to the master’s son. Jesus clearly identifies himself as this crucial character. Notice that nobody else comes to the vineyard after the son. There is no one left to send – no one of higher importance or authority – after the master’s son arrives.

In the same way, our lives hang in the balance according to how we respond to the Son.

Many people find this parable hard to love. After all, it’s seriously out of step with the spirit of our age.

Contemporary spirituality embraces a therapeutic vision of the world – one that promises resurrection without death, joy without sorrow, Easter Sunday without the discomforts of Good Friday. In social critic Ken Meyers’ words, we all become “clients in the hands of a Smiling Heavenly Therapist who is there for us.”

But real life is difficult. The world is a mess.

The awe-inspiring truth is that God offered the life of his Son to begin the process of setting things right.

So what makes Good Friday so good?

The worst thing that ever happened to Jesus has turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to us.