According to historians, what was the most contentious presidential election in American history?

Which election was most deadlocked around questions concerning religion?

And what’s the only election in which both presidential candidates identified themselves as Unitarians?

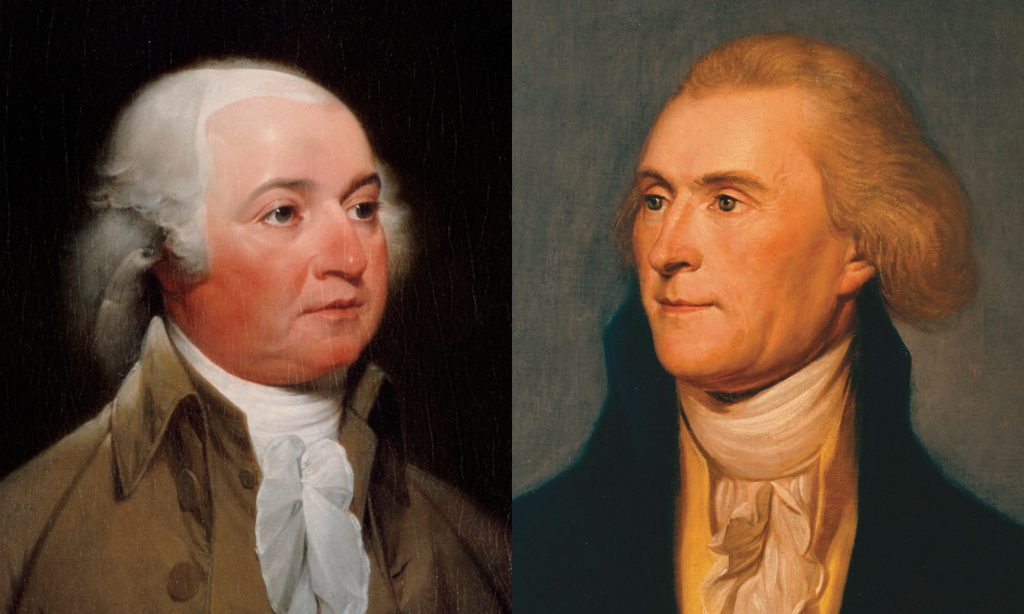

The answer to all three questions is the same: the election of 1800, which pitted the incumbent John Adams against challenger Thomas Jefferson. Because the election of 2020 is the only one that has failed to result in a smooth transition of power, historians may one day hedge on the question concerning “most contentious.” But few would disagree that the supporters of both candidates in 1800 were certain that their rival’s election would result in the ultimate collapse of America.

Two months before voters went to the polls, the Gazette of the United States editorialized: “The only question to be asked by every American laying his hand on his heart is, ‘Shall I continue in allegiance to God and a religious president, or impiously declare for Jefferson and no god?’”

Jefferson’s supporters shot back, arguing that Adams was a dictator who would destroy religious liberty and the rights of conscience. Many of Adams’ voters, after all, had already made it clear they wanted Catholics shipped back to Europe, and hoped that Protestant church membership would become mandatory for citizenship.

Jefferson was smeared as a man with the relational integrity of an alley cat and “an open enemy of Jesus.” His administration would welcome infidels and atheists. Adams’ supporters told their followers to hide their Bibles if Jefferson won, because he would be sending troops to seize them.

Jefferson’s allies countered that he was a far better man than the stocky John Adams, whom they mocked as His Rotundity. He was a more faithful Christian, too. The Virginia planter’s good works clearly exceeded those of the current president.

A pastor wrote that if Jefferson were elected, he would “destroy those morals that protect us from the knife of the assassin, which guard the chastity of our wives and daughters.” The congressional chaplain even declared that a vote for Jefferson was “a rebellion against God.”

If there had been television in 1800, we can only imagine the 30-second political attack ads.

The two men, who had once been good friends, had a seriously falling out as a result of the bitter election. They didn’t communicate with each other again until 1809.

The faith of the Founders was a very big deal 221 years ago. It’s still a big deal today.

As Auburn University professor Adam Jortner points out, the key leaders who guided America through its earliest days were not all Sunday School teachers, as some Christians assert. Nor had they all turned their backs on religion, as some secularists teach. We know that John Jay and Samuel Adams were enthusiastic followers of Jesus, while Thomas Paine and Benjamin Rush thought Christianity was for the birds. George Washington, who generally stayed aloof concerning personal matters, attended an Anglican church but apparently never took communion.

And Jefferson and Adams?

The election of 1800 was cast as the Infidel vs. the Saint. But neither of those labels rang true. Both men later called themselves Unitarians. They respected Jesus but doubted he was divine.

Jefferson narrowly won the election. None of the dire prophecies about him came true. Adams’ supporters got to keep their Bibles, and no one tried to enshrine atheism as our national ideology.

Significantly, the new president acted aggressively to ensure that no religion or philosophy would be officially established. He appointed Jews and Catholics to federal positions. In 1802 he coined the phrase “a wall of separation between church and state.” In our own time, some people lament those eight words. They understand them to mean, “Those who trust God aren’t allowed to influence the culture.”

But that’s not what Jefferson meant. His intent was that no government decree or bloc of voters should ever be empowered to tell churches or synagogues how to manage their own affairs. People of faith (or non-faith) should be left free to follow their consciences without fear of state interference.

Looking back, it’s impossible to imagine U.S. history without the unique leadership contributions of both Adams and Jefferson.

And it’s unimaginable to think that America would have been better off if church membership had become mandatory.

At the heart of the gospel is God’s love for humanity – and his invitation not only to reciprocate that love, but to share it with others.

Real love is persuasive. It is never coercive.

Strange as it may seem, the freedom to say “No” is one of the most important ways for a nation to safeguard the chance for any of its citizens to meaningfully say “Yes” to God.