To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

When most people think of Mary Poppins, they smile.

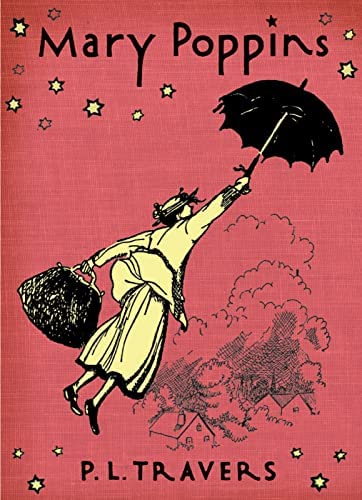

They picture the warm-hearted and charming Julie Andrews starring in the Disney adaptation of P.L. Travers’ famous children’s book. The English nanny, who is “practically perfect in every way,” is blessed with a magic compass, bottomless bag, and an umbrella that allows her to float effortlessly above London’s crowded streets.

If you read Travers’ original volume, however, or any of its eight sequels, you can be forgiven for thinking that Walt Disney made a movie about someone else entirely.

The literary Mary Poppins is, to put it bluntly, not a very pleasant human being. She is stern. And cross. And vain – never passing up an opportunity to admire her reflection in a mirror. At the end of the original book, she doesn’t bother to say goodbye to Jane and Michael Banks, the two children who yearn for her attention and approval. When she passes along her special compass to Michael, he is floored. “There must be something wrong! She has never given me anything before.”

Jane counters, “’Perhaps she was only being nice’… But in her heart she felt as disturbed as Michael was. She knew very well that Mary Poppins never wasted time in being nice.”

She never wasted time in being nice.

Truth be told, Travers’ portrait was entirely consistent with the behavior of parents and caregivers in Edwardian England, roughly the period from 1900 to 1930. Edwardian parents (especially fathers) had a formal relationship with their children. Love and affection were considered unacceptable and even dangerous. Many Baby Boomers will remember that their grandparents grew up in low-touch, low-affirmation environments, and often reproduced that emotional chill in their relationships with their own children.

In his highly regarded 1928 guidebook for parents, Psychological Care of Infant and Child, American behavioral psychologist John Broadus Watson recommended a rigid, disciplinary approach:

“Let your behavior always be objective and kindly firm. Never hug and kiss [your children], never let them sit in your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say goodnight. Shake hands with them in the morning. Give them a pat on the head if they have made an extraordinarily good job of a difficult task.”

It’s no surprise that many children who came into the English-speaking world during the first three decades of the 20th century grew up famished for love.

Travers portrays Jane and Michael’s father as physically and emotionally absent. “Mr. Banks…said to Mrs. Banks that she could either have a nice, clean comfortable house or four children. But not both, for he couldn’t afford it.”

Affluent parents in the Edwardian era customarily handed over parenting responsibilities to nannies. Mary Poppins arrives as a welcome change from the stuffy older women who have always shepherded Jane and Michael. Still, she’s not exactly a warm pillow. When Michael reveals with pride that he has grown two inches, she sniffs that he’s actually grown “worse and worse.” Talk about someone who needs a spoonful of sugar.

It took all of Walt Disney’s charm to talk Travers into letting him produce Mary Poppins as a feature film, complete with music, dancing, and animated penguins – not to mention a title character who was occasionally warm. Travers was not amused. When she saw the final product, she refused to let Disney have the movie rights to the sequels.

What we know for sure is that sternness rarely wins human hearts. But niceness often does.

Sociological studies reveal that nice people enjoy longer and stronger relationships. They live longer. Author Malcom Gladwell cites a study that correlates the niceness of physicians with a lowered likelihood of being sued. Doctors who have never been sued turn out to be those who spend an average of three minutes longer with each patient, compared to doctors who have been sued twice or more. People tend not to want to drag into court people who have been nice to them.

The apostle Paul writes: “Let your conversation be always full of grace, seasoned with salt, so that you may know how to answer everyone” (Colossians 4:6).

In other words, choose to be kind. Choose to be gracious.

For goodness’ sake and God’s sake, be the kind of person who “wastes time” by being nice.

Even without a flying umbrella, you may be the one person who turns somebody else’s lousy day into a hopeful one.