To listen to this reflection as a podcast, click here.

“Impossible” is a relative term.

Sometimes, things we identify as impossible turn out to be quite possible after all.

Over the past 27 years, Tom Cruise’s cinematic hero Ethan Hunt has undertaken six “impossible missions” and somehow succeeded every time. Next month he’ll star in the seventh installment of the action series – a story apparently so bloated with plot twists and special effects that it was impossible to contain it in just one picture. That’s why Part 2 of Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning will be released a year from now.

Some of the world’s greatest scientists have confidently declared certain things to be impossible – only for the next generation to say, “Not so fast.”

Britain’s Lord Kelvin asserted that heavier-than-air machines would never fly, while New Zealand’s Lord Rutherford, “the father of nuclear physics,” assured audiences that generating extraordinary bursts of energy by splitting atoms was “moonshine.” We can only guess how they might have responded if they had been around when an airplane dropped a nuclear bomb in 1945.

As a kid I was an enthusiastic fan of Dick Tracy’s two-way wrist radio. I fantasized a world in which moms wouldn’t have to call their children for dinner by yelling loud enough for the whole neighborhood to hear. Every child could have some kind of portable communication device. But that was impossible – sheer science fiction.

I was wrong, of course. In my own lifetime, every child has potential access to a portable communication device. What currently borders on the impossible is kids choosing to go outside instead of playing video games indoors.

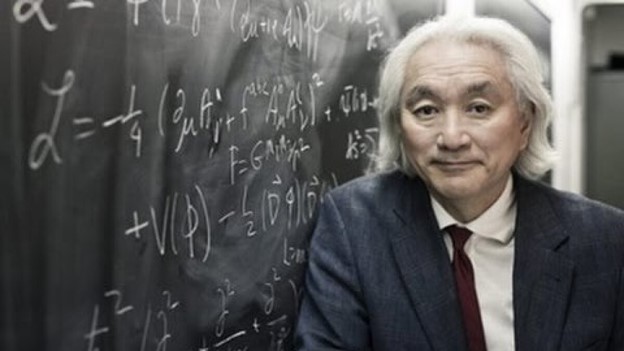

Michio Kaku, one of the world’s foremost theoretical physicists, is well acquainted with the difference between things we only think are impossible and those that can never actually happen.

Kaku, a second generation Japanese-American, has always had audacious ambition. For his high school science fair project, he built a makeshift atom smasher in his mother’s garage. He then wound 22 miles of copper wiring around his school’s football field, creating a magnetic field 20,000 times stronger than the Earth’s. That allowed him to generate a gamma ray beam powerful enough to create antimatter. And you thought it was pretty awesome when your science fair project conclusively demonstrated that plants that get water and sunshine do better than those that don’t.

In his delightful 2008 book Physics of the Impossible, Kaku divides so-called impossibilities into three categories.

Class One includes technological achievements that are impossible today, but which don’t violate the known laws of physics. These include teleportation (“beam me up”), invisibility, starships that can approach the speed of light, and something akin to the galactic empire’s Death Star in Star Wars.

Class Two accomplishments take us to the very edge of our understanding of the cosmos. These are theoretically possible, but may be thousands of years away from realization. Here we’re talking about time machines and zipping between opposite corners of the universe via “wormholes.”

Class Three impossibilities are just that: genuine impossibilities. They violate the known laws of physics. This is the right spot for perpetual motion machines (the real-life equivalent of an Energizer Bunny, which keeps going and going without needing a source of energy) and the ability to see what will happen in the future.

Kaku’s conclusions are based on the assumption of a “closed universe.” What you see is what you get – the material universe and nothing more. In the words of fellow astrophysicist Carl Sagan, “The cosmos is all there is, all there ever has been, and all there ever will be.”

That, of course, is a stunningly transparent bit of religious dogma. It is an a priori statement – a philosophical assumption that is made apart from empirical observation, and that cannot be confirmed by telescopes and test tubes.

The Bible’s authors operate within the perspective of an “open universe.” The cosmos is still there, exactly as materialists find it. But it’s not necessarily the only thing that exists. The assumption of an open universe leaves open the possibility that there is an invisible or supernatural realm – and that there can be connections between the two within space and time.

And that casts a new light on the word “impossible.”

A Galilean peasant girl named Mary, for instance, is staggered by the notion that she might become pregnant apart from interaction with her fiancé. Such things just don’t happen. But the angel Gabriel assures her, “With God, nothing will be impossible” (Luke 1:37).

When Jesus tells his disciples that it will be easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to get into heaven, they are shocked. And not a little afraid. “Who, then, can be saved?” Jesus replies, “From a human standpoint this is impossible, but with God, all things are possible” (Matthew 19:26).

What we cannot accomplish in our own wisdom and strength is clearly right up God’s alley.

The most important New Testament verse on this subject appears in the book of Hebrews. The author points out that when God made a promise to Abraham, he was never going to take it back. That’s because “it’s impossible for God to lie” (Hebrews 6:18). This has nothing to do with the laws of physics. It’s conceivable that God could alter the “rules” of the cosmos. But God cannot cease to be God. He cannot violate his own character by reneging on a promise.

That’s why the very next verse says, “We have this hope as an anchor for the soul.”

And Hebrews 6:19 is why, whenever we see an anchor in a stained-glass window or a medieval work of art, we can know that the artist is conveying something about Christian hope.

Another celebrated theoretical physicist, Niels Bohr, was fond of saying, “Prediction is very hard to do. Especially about the future.”

True enough.

But here’s a trustworthy forecast concerning every one of our own tomorrows: God will never forsake those who abandon themselves to Jesus.

That would truly be impossible.